Safety Glass – Types, Standards, and Reporting.

In this article, we look at some of the different types of glass used in residential property, the standards of safety glass, and the reporting requirements of residential surveyors.

Why is safety glass so important?

‘Safety glass’ is toughened or laminated so that it is less likely to splinter when broken, as well as less likely to break, compared to non-safety glass. Injuries caused by broken glass are relatively common in the UK. Broken glass from bottles, windows and glass doors can be extremely serious and lead to long-term scarring and serious lacerations, and even, albeit in extreme circumstances, death.

Ola Brunkert, the drummer of ABBA, died after falling through a glass door at his house in Spain in 2008. He had hit his head against a glass door in his dining room, which made the glass shatter and caused serious cuts in the back of his neck. Despite horrendous injuries, he had managed to wrap a towel around his neck and leave the house to seek help but collapsed in the garden.

Consequently, it is important to use safety glass in certain situations to reduce the risk of injury to occupants and users of a building/space.

Surveyors should therefore be able to identify ‘critical location’ where use of safety is recommended, identify whether it is actually safety glass and recommend when action is required to reduce any risk.

What is safety glass?

The most common glass used today is Float Glass. The ‘Float Process’, where a continuous ‘ribbon’ of flat glass is formed on a bath of molten tin creating a glass that does not require polishing, was developed by Sir Alastair Pilkington in 1952. This enabled larger and more consistent panels of glass to be manufactured than previously. Float plants now produce glass panels up to 3 metres in width and between 0.4mm and 25mm thick. However, this glass

product would be relatively fragile (cracking with a change in temperature or a small physical shock) unless it is ‘annealed’ at the end of the float process.

Annealing is where metal or glass is allowed to cool slowly, in order to remove internal stresses and toughen the final material by relieving any internal stresses in the glass. For example, copper tubing will be brittle if it is not cooled correctly after bending.

This ‘annealed glass’ is a product formed from the annealing stage of the float process and is used as a base product to form more advanced glass types.

Tempered (or toughened):

Tempered (also known as toughened) glass is annealed glass that has been processed by controlled thermal or chemical treatments to increase its strength. The finished ‘toughened’ glass is much stronger than annealed glass. When tempered glass breaks, it does so into small, regular, typically square fragments rather than long, dangerous shards (the name of the Shard building in London references these shapes). For this reason it is the most common glass used for architectural applications such as balustrades.

Laminated:

Laminated glass consists of two layers of glass with a plastic film bonded in between them. If the glass breaks, the plastic film will hold the glass safely in position. Basic annealed glass can be laminated, but so can toughened glass. Laminated glass is commonly used where there is a security issue – the bonding film holds the glass together if it is broken. The strongest security glass can withstand close-range impact from explosives and guns.

Wire glass:

This glass includes a wire mesh to hold it in place if it breaks. Wire glass is used in fire-rated windows and doors as it meets most fire codes, However, it is not strengthened glass and is not safety glass.

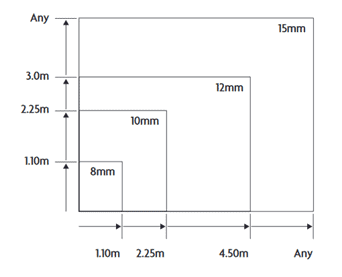

Thickened Annealed glass gains its strength through its thickness. It is cheaper than other types of glass as it hasn’t been through any additional manufacturing processes to strengthen it. The maximum dimensions for annealed glass of different thicknesses for use in large areas forming fronts to shops, showrooms, offices, factories and public buildings with four edges supported is shown in the below diagram, taken from Approved Document K.

Figure 1: Annealed glass thickness and dimension limits (taken from Approved Document K)

There is useful additional information on the types of glass here https://www.basystems.co.uk/blog/glass-types/

Glass blocks and polycarbonates

Approved Document K describes polycarbonate and glass blocks as inherently strong. Glass blocks became a popular design choice in the 1930s and 1940s, especially for bathrooms, and they are even making a comeback today.

Although not glass, polycarbonate is a popular material choice for greenhouses.

Building Regulations

Since 1 April 2002, Building Regulations have applied to all replacement glazing and cover thermal performance and other areas such as safety, air supply, means of escape and ventilation. Previously in Approved Document N, the Building Regulations relating to glass are now in Approved Document K – Protection from falling, collision and impact, and explained under “Section K4, protection against impact with glazing”.

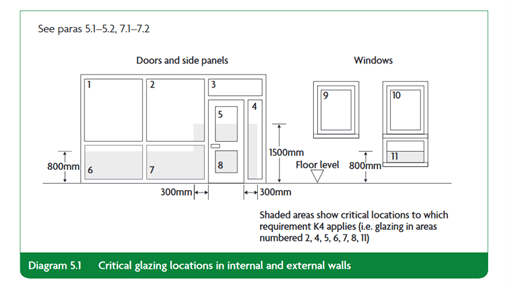

The Building Regulations require that glass fitted in critical locations such as in glazed doors, side panels and areas below 800mm is safe.

Surveyors need to inspect, measure and record all glazing types in their site notes so they can confirm that any glass windows and doors comply with the requirements above.

Below is an extract from Approved Document K explaining the safe breakage requirements and standards for glazing:

Safe breakage

5.3 Safe breakage is defined in BS EN 12600 section 4 and BS 6206 clause 5.3. In an impact test, a

breakage is safe if it creates one of the following.

a. A small clear opening only, with detached particles no larger than the specified maximum size.

b. Disintegration, with small, detached particles.

c. Broken glazing in separate pieces that are not sharp or pointed.

5.4 A glazing material would be suitable for a critical location if it complies with one of the following.

a. It satisfies the requirements of Class 3 of BS EN 12600 or Class C of BS 6206.

b. It is installed in a door or in a door side panel and has a pane width exceeding 900mm and it

satisfies the requirements of Class 2 of BS EN 12600 or Class B of BS 6206.

BS 6262 is a series of standards on glazing for buildings. BS 6262-4 gives safety recommendations for the use of glass and plastic glazing sheet materials in locations likely to be subject to accidental human impact. BS 6262-4 also gives recommendations for the type of glass or plastic glazing sheet materials to be used in sloping overhead glazing.

The recommendations are intended to reduce impact-related injuries and in particular the risk of cutting and piercing injuries. In the case of sloping glazing, this also covers the risk from falling glazing.

NOTE: These recommendations do not apply to: glazing for furniture and fittings, glazing for commercial greenhouses, glazing for domestic greenhouses.

The below numbers are product numbers that identify the type of glass:

- BS EN 12150 – to identify toughened glass

- BS EN 14449 – to identify laminated glass

- BS EN 14179 – to identify heat soaked, thermally toughened glass.

How can you tell if it’s safety glass?

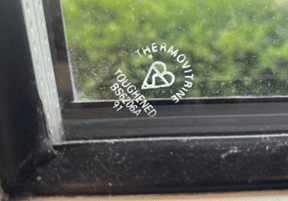

Safety glass needs to be permanently marked and the marks must be visible to the eye after installation.

The NHBC has a useful technical guidance document on the marking of safety glass: https://www.nhbc.co.uk/binaries/content/assets/nhbc/tech-zone/nhbc-standards/tech-guidance/6.7/marking-of-safety-glass.pdf

It explains:

The comparisons between the classification systems under BS 6206 and BS EN 12600 are shown below. Both BS 6206 and BS EN 12600 use pendulum impact tests with similar drop heights and grades safety glass under one of

three impact performance

classifications.

- BS 6206 grades are ‘A, B or C’ with ‘A’ being the highest performance grade.

- BS EN 12600 grades are ‘1, 2 or 3’ with ‘1’ being the highest performance grade.

For comparison purposes between the two Standards grade ‘A’ = ‘1’, ‘B’ = ‘2’ and ‘C’ = ‘3’.

To identify the grade of safety glass used each pane should be indelibly marked so that the marking is visible after installation.

The markings should include:

- The manufacturer’s name or trademark

·The product number for the type of glass *

·The impact performance classification e.g. 1, 2 or 3 to BS EN 12600 or A, B or C to BS 6206.

* e.g. BS EN 12150 toughened glass, BS EN 14449 laminated glass, BS EN 14179 heat-soaked thermally toughened glass

Figure 2: Example of safety glass mark

Figure 3: Example of toughened safety glass

In practice, not all safety glass will be marked, and if you come across glass that isn’t marked, it would be safer to assume that it isn’t safety glass unless there is evidence to confirm otherwise. Wherever you come across ‘issues that potentially impact safety’ a good mantra to adopt is better safe than sorry.

BSI Kitemark

BSI Kitemark is an established quality mark that shows a particular product meets the applicable and appropriate British, European, international or other recognised standard for quality, safety and performance and the BSI tests and certifies a range of different glass products.

There is more than one BSI Kitemark for glass reflecting the different processes and applications.

Here is a sample from some manufacturers’ product specifications.

- BS 6180: 1999 – Code of practice for barriers in and about buildings.

- BS 6206: 1981 – Specification for impact performance requirement for flat safety glass and safety plastics for use in buildings.

- BS 6262: 1982 – Code of practice for glazing for buildings.

- BS 6399: – Loading for Buildings – All Parts.

- BS EN 12150-1:2015 – Glass in building – thermally toughened soda lime silicate safety glass.

BSI standards do not remain constant – some will be retired or updated as the industry changes. The BS numbers most residential surveyors will see are BS 6202 and BS EN 12150.

What is unlikely to be safety glass?

Horticultural glass is the lowest grade of glass produced and therefore, the cheapest. It’s considered dangerous because if it breaks, the shards tend to be large, dangerous pieces which are very sharp and can inflict serious injury. Many greenhouses are made with horticultural glass, especially older greenhouses, and Building Regulations do not apply to greenhouses found in the gardens of domestic properties, so this should be considered if you are assessing a property with a greenhouse on the grounds.

Reporting

As a surveyor, it is our duty to report on any glazing that we inspect doesn’t meet current safety standards, notwithstanding the age of the property. The RICS Home Survey Standard lists “absence of safety glass to openings and outbuildings” as a common safety hazard that can be found during an inspection of a residential property. If it isn’t safety glazing, it is a potential health and safety hazard, and your clients should be notified. This should be included in the appropriate section of the report and cross-referenced in the health and safety section. It may also be prudent to inform the current occupiers of the potential hazard.

Whilst absence of safety glass in critical locations is a hazard, such absence should not automatically result in a CR3. A significant proportion of dwellings have non-safety glass fitted, and the properties are not replete with severed limbs or bodies.

People have been living within non-safety glass for centuries, but as suggested above, where issues of health and safety are concerned it is better to be safe than sorry. A suggested approach to applying condition ratings might be that set out in the Sava Condition Rating Protocol.

Briefly, the surveyor should note, record and report on every hazard ‘in’ or that ‘could affect’ people in the property so long as that potential hazard is not too remote. The best benchmarks to identify hazards are in the Building Regulation Approved Documents (BRADs). The client is then aware of those hazards.

However, the surveyor should also make a decision about whether the resultant hazard requires appropriate action to be taken i.e is the hazard a CR2 or a CR3? To do this, a simple risk assessment based on ‘likelihood’ and ‘severity’ can be recorded. This does not need to be longwinded or too onerous. Indeed, in time, surveyors will find a standardised risk assessment process is helpful. Once you have risk-assessed one glass door, a similar process for similarly situated doors can be applied.

Conclusions

Surveyors and the reports they produce directly affect people’s lives. By correctly inspecting, identifying, recording and reporting on safety (or non-safety) glass (and indeed other hazards that may be present) we can help ensure our clients’ lives are positively affected.