Ash v Powell – A Lesson for Surveyors.

In February 2020 the Evening Standard reported on a case where a couple selling their home in Oxfordshire, and who failed to tell the buyers about the plans for a new motel nearby, were found liable and ended up facing a legal bill of up to £300,000 (source here).

The reason this story hit the Evening Standard, The Telegraph, and the Oxford Mail, among others, was that the property was “a stunning barn conversion with excellent equestrian facilities”, worth in excess of £1 million and the new motel in question was Mollies Motel, developed by Soho House, the exclusive members club favoured by celebrities. The opening of Mollies was attended by Jeremy Clarkson, Paloma Faith, and Declan Donnelly, among others.

While this case involved just the sellers and purchasers, it does raise questions about the application of the new RICS Home Survey Standard (HSS) which come into force on the 1 March 2021.

In this article, Hilary Grayson and Nik Carle look at the case and consider how the new RICS HSS might have impacted a case such as this (if the HSS had been in force). What if the purchasers had happened to commission a level three service with the HSS in effect?

Philip Ash and his wife Elisabeth advertised their property as located in Oxfordshire and had agreed on a sale with Adrian and Lisa Powell.

However, they did not reveal that plans had been approved for a fifties-style diner and upmarket motel with flood-lit car park and neon signs on adjoining land, despite leading objections to the development themselves.

Background

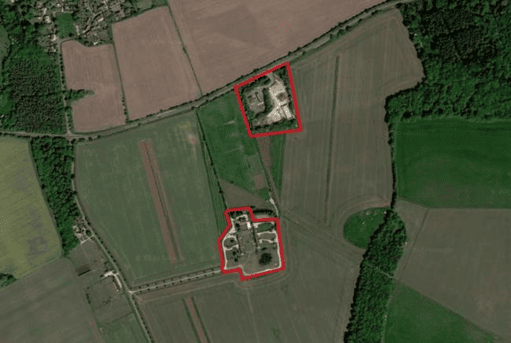

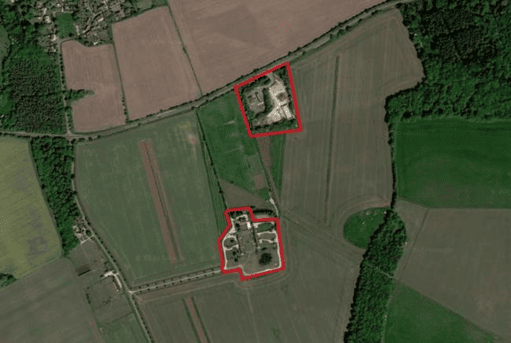

Lake Barn is a 4-bed barn conversion with a separate home office and just under 4 acres of land situated approximately 5 miles from Farringdon in Oxfordshire. It was described as a “substantial period family house located in an exceptional rural position, with large gardens, far-reaching views and excellent equestrian facilities.” On sales particulars drawn up in 2013, it is further described as being set within particularly attractive surrounding countryside, offering many opportunities for walking, riding, and golf.

In this case, the purchasers had been searching for a suitable rural property for some time. They agreed to buy the property in 2017, for just over £1 million. The conveyance proceeded in the normal way. There was an exchange of contracts and the purchasers paid a deposit of £108,500.

However, unbeknown to the purchasers, in 2016 the local authority had granted planning consent for an old roadside property adjacent to Lake Barn to be converted to an American style diner and motel.

The sellers were aware of this development, having objected to it when the planning application was made, but they failed to declare it on the sellers’ questionnaire.

Following the exchange of contracts, the purchasers found out about the development and pulled out of the deal. They sued the sellers for the return of their deposit and damages. The sellers refused, and the dispute went to court. The sellers insisted they had filled in the questionnaire truthfully, believing it only applied to the house.

Judge Monty said the sellers had not tried to “cheat or deliberately mislead”, but it was clear their answer was wrong. He found that they knowingly put false information on a sellers’ questionnaire and found that they were liable to repay the deposit plus costs, expected to be more than £175,000.

The motel, complete with pink neon signs spelling out “Mollie’s Motel & Diner”, was built and opened in January 2019.

The house eventually sold to another buyer at a reported figure of £985,000.

So, what has this got to do with surveyors?

In this case, no surveyor was employed by the purchasers, but what if a surveyor had been employed and working under the new Home Survey Standard?

When it comes to “knowing your area”, the new HSS states at Section 3.1:

“RICS members must be familiar with the type of property to be inspected and the area in which it is situated.

The depth and breadth of the research will depend on a range of factors including the RICS member’s knowledge and experience, the locality and the client’s specific requirements. At levels one and two, the amount of research is likely to be similar. Research for level two services on older and/or complex properties, historic buildings and those in a neglected condition, and all level three services is likely to be more extensive, and also if the client has requested additional services.”

This is expanded in Appendix C:

“RICS members need to be familiar with the nature and complexity of the area in which the subject property is located. This includes general environmental issues where the information is freely available to the public (usually online). The nature, quality and accuracy of the data varies between suppliers and so RICS members should treat this information with care. Although the range and nature of these issues will change over time, the list currently includes:

- Flooding (surface, river, and sea)

- Radon

- Noise from transportation networks

- Typical geological and soil conditions

- Landfill sites and relevant former industrial activities

- Former mining activities

- Future/proposed infrastructure schemes and proposals

- Planning areas (e.g. Conservation areas, areas of outstanding natural beauty and Article 4 direction)

- Listed building status and

General information about the site including exposure to wind and rain, risk of frost attack, and unique local features and characteristics that may affect the subject property.”

It goes on to say that the list is not exhaustive and that relevant issues will vary based on location.

Knowing your area is one thing, but what should you be reporting to the client and, how might this vary depending on the level of service offered?

Section 4 of the new HSS deals with what should be included in the report and specifically 4.3.1, 4.3.2 and 4.3.3. cover level one, level two, and level three surveys, respectively. (note: see boxes at end of the article)

However, section 4.6 then goes onto cover legal matters. It makes it very clear that the RICS member will be the eyes and ears of the legal adviser appointed by their client. They must highlight the relevant legal matters and remind the client that they should bring these legal matters to the attention of their adviser. Some examples are listed under section 4.6.1:

- conservation areas (especially Article 4 designation), listed building status and the need for consents

- work done under the various ‘competent persons’ schemes

- planning permission and building regulation approval for alterations and repairs, and any indemnity insurance policies for non-compliance (if known)

- trees and any tree preservation orders

- environmental matters, such as remediation certificates for previously contaminated sites and whether a mining report is required and

- the use of adjacent, significant public or private developments

Section 4.6.2 covers guarantees, but 4.6.3 then covers other matters, stating that “…other features and issues that may have an impact on the property and require further investigation by the legal adviser” should be included. A list of possible topics this might cover is listed in Appendix F:

“RICS members should include other features and issues that may have an impact on the subject property and require further investigation by the legal adviser. The following list (which is not exhaustive) illustrates this variety:

• flying freeholds or submerged freeholds

• evidence of multiple occupation, tenancies, holiday lettings and Airbnb

• future use of property

• signs of possible trespass and rights of way

• arrangements for private services, septic tank registration and so on

• rights of way and maintenance/repairing liabilities for private access roads and/or footways, ownership of verges, village greens and so on

• chancel matters

• other property rights including rights of light, restrictions to occupation, tenancies/vacant possession, easements, servitudes and/or wayleaves

• boundary problems including poorly defined site boundaries, repairs of party walls, party wall agreements and works in progress on adjacent land

• details of any building insurance claims

• parking permits

• presence of protected species (for example bats, badgers, and newts) and

• Green Deal measures, feed-in tariffs and roof leases.”

Interpreting the Home Survey Standard

Thinking about the Lake Barn case from a surveyor’s liability perspective, it is important to consider how the new RICS Home Survey Standard might have been interpreted and how such interpretation might have impacted in a case such as this. What if the purchasers had commissioned an HSS level three service, or even a level two service without a valuation?

Surveyor knowledge of the locality is key. There MUST be familiarity with the area. As we have seen, the HSS is clear on this: surveyors MUST undertake appropriate pre-inspection research.

Historically, it is the authors’ view that many “building surveyors” would argue that a condition report (or traditionally a building survey) is just about the physical aspects of the property. Yes, they have always needed local knowledge, for example, to cover issues such as flooding or mining etc. but this knowledge is just about identifying things that could affect the property physically. However, when it comes to something such as neighbouring land use which has no impact on the physical aspects of the property (though it could have an impact on value), then many traditional surveyors would insist that this was not part of their remit.

Whatever historically has been accepted practice relating to level 2 or 3 condition surveys, considering the HSS in the context of this particular case suggests that a surveyor should take into account local planning consents when delivering a condition report at level 2 or 3. This is particularly pertinent where, as with this case, the planning intention “nearby” was publicly available information. Conveyancing practitioners are unlikely to be subject to requirements of “familiarity” and “knowledge” of the area/locality to the same degree as surveyors. The responsibility will sit squarely with the surveyor.

Additionally, surveyors may also now need to consider matters on “land nearby” as well as on “neighbouring properties”. “Land nearby” is a significantly more extensive responsibility than merely neighbouring property.

Appendix C of the HSS covers environmental factors or those which have potential physical impact. However, as we have seen, it does also include knowledge of proposed/future “infrastructure schemes” and by implication the knowledge of “planning areas” (particularly as Appendix C is clearly stated to be not prescriptive or exhaustive).

There also appears to be an emphasis in the HSS on whether or not relevant data is “publicly available”. Where key information IS publicly available, it may be more difficult for surveyors to justify excluding this from their pre-inspection research or the report even if the knowledge in question has no potential impact on the physical aspects of the subject property.

Our conclusion is unequivocal: even if previously surveyors have only been used to reporting on the “bricks and mortar” alone, in future they will have a responsibility to bring environmental/location matters to the attention of their clients (at least for further investigation by the legal representative), even if the potential impact of such matters is only on value and not the ongoing physical performance of the property.

Hilary Grayson

Hilary is focused on developing new qualifications, as well as Sava’s activities within residential surveying. Hilary has a wealth of experience within the built environment, including commercial property, local government and working at RICS. As well as her work at Sava, she is a Trustee at Westbury Arts Centre, a listed farmhouse dating from the Jacobean period, and has inadvertently become a custodian of a colony of bats.

Nik Carle

Nik is an experienced professional negligence litigator, acting for and against advisers across the full business spectrum, with a focus on claims involving solicitors, brokers, surveyors, valuers, and estate agents. Nik also advises on complex insurance policy disputes. Nik is also a qualified arbitrator and is admitted as a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (FCIArb). He is listed on the CEDR Panel for commercial arbitration work, accepting contractual and ad-hoc appointments for business-to-business disputes. As an ADR Official, Nik has adjudicated on over 500 consumer disputes, across CEDR’s Aviation, WATRS and CISAS Schemes.