Cast Iron Houses.

As a Chartered Surveyor, I often find myself feeling very honoured and fortunate in my role. Not only do I love what I do, but I also have the privilege of seeing some fascinating historic buildings. From historic period timber framed, through to present day Modern Methods of Construction built properties, there is never a dull day.

Add to this the fact that I live and work as a residential surveyor within the Midlands region. I am at the very heart of the region that has the claim of being the ‘birthplace of the Industrial Revolution’. Consequently, I often find myself coming across fascinating buildings of all types from both a historical and architectural perspective. One such property, is the Cast Iron House.

As with many vernacular buildings, over the centuries locally sourced materials and the local construction methods used were fundamental to the building process. As well as more historic buildings, we can see evidence of this through the Victorian period right up to the Second World War. In the modern 21st century, we often look back and reminisce of buildings pre and post war and recently I came across a pair of semi-detached houses built circa 1925 which are a fine example of local imagination and resource, and a testimony to local ingenuity.

Figure 1 – semi-detached cast iron houses in Dudley

A brief history lesson

Following on from the end of the First World War, there was a shortage of housing and traditional building materials. Speed and ease of construction were important aspirations for house building, especially given population levels and the skill shortage. The National Government also sought to encourage building more homes for the working classes returning after the horrors of the First World War under the ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ initiative. Engineers and local building firms were tasked with embracing innovation and development to meet the requirements of the country’s housing needs.

It was hoped that by using iron for building houses, not only would it help to fulfil these requirements, it would kick start the local iron industry which was struggling at the time, both in terms of work shortage and a lack of skilled labour. The result? One of the first prefab houses! It’s suggested that it only took 4 workers a total of one week to complete the build and it is believed that there were approximately 500-600 of these property types built throughout the UK between 1925-1928.

Ultimately, they were an experiment in using iron to pre-fabricate buildings and, sadly, only four were ever built in the local area. Why? Well, put simply, cost. In 1925 money terms, at c.£1,000, these semi-detached houses cost twice as much as traditionally built masonry houses.

Homes Fit for Heroes

After the horrors of WW1, Lloyd George delivered a speech the day after the armistice where, amongst other promises, he said there would be “Habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war”. This was translated into the pithier slogan “homes fit for heroes” where “homes” and “fit” implied they would be built to a standard beyond some of the outdated Victorian slums and “heroes” implying a sense of gratitude and deserving.

The legislation that followed this ‘promise’ was well meaning but was hampered by two serious problems: the lack of funds and the extreme shortage in the building industry of skilled manpower and materials.

The government also had to address social unrest and the fear of Bolshevism spreading from Russia. From 1917, industry and the docks had been hit by some damaging strikes. Improving the lives of the working population was, therefore, not just a ‘good thing to do’ but also had a political motive.

The Ministry of Reconstruction was set up in 1917, the term “reconstruction” being in the context of the reconstruction of how government was organised. It was “charged with overseeing the task of rebuilding the national life on a better and more durable foundation”.

Its recommendations covered many subjects, including: a more efficient government administration; women’s roles post WW1; housing; industrial relations; and employment. The main impact on post-WW1 housing was to create a Ministry of Health under which social housing and slum clearance were managed, with a housing department and local commissioners being in control.

The government also appointed architect and MP Sir John Tudor Walters to report on the condition of housing. The result was the “Report of the Committee Appointed to Consider Questions of Building Construction in Connection with the Provision of Dwellings for the Working Classes”, shortened simply to “The Tudor Walters report”. This influential report made recommendations for the design of housing and housing estates. These designs were specifically to:

- Set minimum expected building standards and facilities (such as a bath in every house);

- Provide house designs that would be both pleasant to live in yet economical with scarce building materials; and

- Provide useful guidance as to the layout of a scheme (for example, to build housing in cul-de-sacs. The number of houses that could be fitted would not change but there would be cost savings on road-building when compared to a through road).

The Housing Acts of 1919 and, later, 1923 introduced complicated financing mechanisms, with the later act very much encouraging private companies building on behalf of local authorities and generating the social housing boom that continued to the 1930s.

Construction

The houses were constructed from 600 rendered, cast iron rectangular blocks (yes 600, weighing an estimated 14 tonnes!), which were bolted together and would have originally been lined with asbestos insulation panels. The internal cavities were filled with compressed waste wool and the roofs were traditionally Welsh slate; however, interlocking clay tiles were also used.

Figure 2 – Welsh slate roof

Figure 3 – Internal view of some of the 600 cast iron panels bolted together

The outside of the houses required (and still do) painting every 3-4 years to prevent rusting and corrosion of the steels. They were painted white to keep them cooler in the summer months.

Figure 4 – View of the external painted wall panels, showing early stage corrosion to joints – this is why they are re-decorated regularly to prevent further, more serious deterioration

A concrete ground beam formed the substructure which was stepped internally forming a kerb to support the floor joists and splayed externally to form water shed.

Figure 5 – splayed concrete ground

Figure 6 – kerb to support the original floor joists (since concreted as part of the modernisation works)

Setting the bar

What makes these houses so special, in my opinion, is that they are not only one of the earliest examples of prefabricated houses in the UK, but they helped to underpin many non-traditional iron and steel houses that followed years later. During the 1950-1960 period following the Second World War, due to a notable shortage of both material and labour (once again), we went on to see a modern evolution of these cast-iron houses, with the introduction of the more popularly mass produced BISF (British Iron and Steel Federation Houses). Within the Birmingham conurbation alone, it’s believed there were some 500 BISF houses built, many of which are still occupied today.

Figure 7 – Example of BISF house

Figure 8 – Example of BISF house

To get an understanding of the numbers, in Birmingham, there are approximately 112,000 council dwellings. Of these, 22,000 are in blocks of flats, being 422 blocks in total. Of the total there are 22,000 low and medium rise properties of non-traditional construction, ranging across 49 different system types. At the time of my research 44,000 of the 112,000 properties were non-traditional.

It’s fair to say that the evolution of buildings during the 1920s through to the 1960s was one of the most innovative periods ever witnessed within the UK. This period led to mass production of experimental homes of all shapes and sizes with all sorts of designs, including PRC (Precast Reinforced Concrete) and poured in-situ concrete, steel framed and clad, timber framed, cross wall and modular framework to name but a few.

Metal framed – Some 140,000 such dwellings have, at some time or other, been authorised for construction in the UK (of which several different systems have been used)

Pre-cast concrete – It’s understood that around 284,000 dwellings in England have concrete panels as their predominant wall structure

In-situ concrete – Some 332,733 cast-in-situ concrete systems have been built between the 1940s-1970s (with nine different system types noted)

Timber framed – Between 1920 and 1944 some 8,000 timber framed dwellings were built for the UK Public Sector with a further 100,000 built between 1944 and 1975 – many of which have restricted lending terms or may even be unsuitable for mortgage lending

Problems Unforeseen

Innovation was certainly achieved; however, what couldn’t be foreseen when building using some of these construction methods and non-traditional materials, was the potential for structural failure in years to come. In the early 1980s, investigations by BRE following a fire at an ‘Airey house’ (constructed of aggregate PRC panels) found that the PRC columns had cracking present, reported to be caused by inadequate cover to the embedded steel reinforcement and chemical changes to the surrounding concrete. Investigations revealed that it wasn’t just the Airey house that had these defects and a list of 30 post-war, non-traditional house types were also ‘Designated as Defective’. The government introduced the Housing Defects Legislation, which now forms part of the Housing Act 1985, and a Scheme of Assistance was subsequently launched whereby local authorities assisted eligible owners who were able to repurchase or have their property repaired. A small number of properties exist today which haven’t been repaired and are still deemed as defective.

Considerations for the Surveyor

There are many factors to consider when surveying and valuing non-traditional properties. For instance:

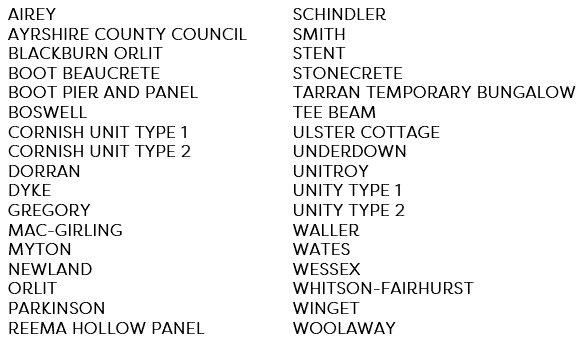

- Are they designated as ‘Defective’ under the Housing Defect Legislation of 1984?

See figure 7 for a list of house types which are Designated as Defective - Have they been subject to a licensed repair works scheme? Repairs must be carried out in accordance with a PRC Homes Ltd licenced system. If subject to a mortgage valuation, is the repair scheme acceptable to the lender?

- Some mortgage lenders will require satisfactory comments from a Structural Engineer or Chartered Building Surveyor prior to when the lending decision is ultimately made

- Is there ready demand and evidence of re-saleability within the locality? A little research will verify if similar properties have been sold. But also, bear in mind that cash purchasers and buyers who require a mortgage may have different experiences

- What condition is it now found in and has it been maintained?

Research suggests, that in the Birmingham region alone, there are around 6,000 privately owned, defective house types still in occupation today so caution is required - Check the roof space! This is often one of the easiest places to confirm the construction type. Measure the wall thicknesses too and take plenty of photos of key construction details – post inspection diagnosis is often easier with colleagues back in the office if you’re unsure!

Figure 7 – list of Designated Defective house types

Many potential buyers of such dwellings may find that further investigations are necessary to determine the condition of hidden components and structural integrity. It’s therefore essential to seek professional, local expertise at the earliest opportunity.

About Ian Bullock Bsc (Hons) MRICS MEWI, Carpenter Surveyors

Ian Bullock is Managing Director of Carpenter Surveyors, a Midlands based Chartered Surveying practice established for over 30 years, specialising in the provision of Residential Survey and Valuation services to both private individuals and financial institutions.