Energy Performance Certificate and Value.

This year, one of the major high street lenders introduced new valuer guidance asking valuers to consider the EPC in their valuation process. We are writing this article as COP26 Glasgow has just completed.

With the UK government committing itself to cut greenhouse gas emissions to “net-zero” by 2050 (June 2019), stating an ambition for as many homes as possible to be EPC band C by 2035 (the average energy rating band for properties in the UK is D) and climate change shooting up the agenda, now is the time to consider EPCs, how they might impact values in general, and to question the role of the residential surveyor and valuer to help the UK hit its net-zero targets.

Net-zero means that in 30 years’ time the UK commits to emitting no more greenhouse gases than it takes out of the atmosphere, to keep the UK in line with the commitments it made as part of the 2016 Paris Agreement to keep global warming under 2 degrees.

A brief history of the EPC

EPCs were originally included as part of the Home Information Pack (HIP) introduced by the Housing Act 2004 and The Energy Performance of Buildings (Certificates and Inspections) (England and Wales) Regulations 2007 (S.I.2007/991) after the introduction of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD). The EPBD is an EU directive on the energy performance of buildings. The implementation is still an important part of the strategy to tackle climate change. In 2010 the EPBD was recast, Home Information Packs were no longer mandatory, and the role of the EPC was strengthened. The European Commission explained:

“The Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) are important instruments that should contribute to the enhancement of the energy performance of buildings. EPCs play a central role in the context of the Article 20 (2) EPBD, which asks Member States to provide information on the energy performance certificates and the inspection reports, on their purpose and objectives, on the cost-effective ways and, where appropriate, on the available financial instruments to improve the energy performance of the building to the owners or tenants of the buildings.”

The purpose of the EPC

As quoted by the European Commission, the purpose of the EPC was to provide information on cost-effective ways (and available financial instruments, where appropriate), to improve the energy performance of the building. In the UK, an EPC is needed whenever a property is built, sold, or rented (although listed buildings are exempt).

Over the years, and as regulation has changed, the EPC has been used in various schemes and incentives such as the ‘Green Deal’ scheme, the ‘Renewable Heat Incentive’ scheme (RHI), and the ‘Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards’ (MEES).

Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES)

In 2018, the MEES for privately rented properties was introduced. MEES means that from 1 April 2020, landlords cannot let or continue to let properties covered by the MEES Regulations if they have an EPC rating below E unless they have a valid exemption in place. (The rental market is currently the only market that imposes minimum energy efficiency standards.)

That said, there is a cost cap currently set at £3,500 (including VAT) on energy efficiency improvements and if a property cannot reach EPC E within this sum, then the landlord can make all the possible improvements up to that amount and then register an ‘all improvements made’ exemption. Read more on MEES here.

The Clean Growth Strategy

In 2017, the government published a strategy that set out the actions it would take to cut carbon emissions, increase efficiency, and help lower the amount consumers and businesses spend on energy across the country. This “Clean Growth Strategy” defined clean growth as growing the national income while cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

The strategy dealt with more than just buildings and reported on ‘green jobs’ (including green energy generation) and transport etc.

The Heat and Buildings Strategy

In October 2021, the government published the “Heat and Buildings Strategy” which sets out the latest vision for a green future and how the UK will decarbonise our homes and our commercial, industrial and public sector buildings as part of setting a path to net-zero by 2050.

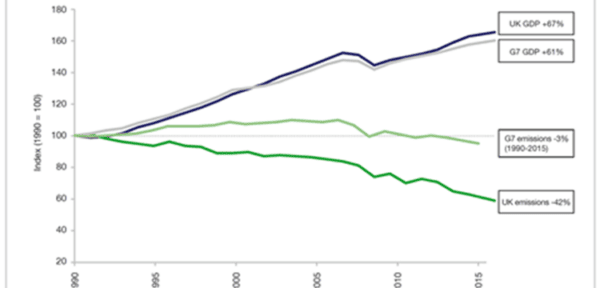

As the graph below shows, overall, the UK’s carbon emissions—from all sources—have already fallen by 43% since 1990. This is largely accounted for by the decarbonisation of the electricity grid and improvements in energy efficiency. Sometimes it is easy to think we’re not making any progress against these massive carbon reduction targets. But as this demonstrates, we are.

Our performance has not been so bad, particularly if you compare our performance to other G7 economies.

Figure 1: UK and G7 economic growth and emissions reductions

According to the Clean Growth Strategy, in 2016, 47 per cent of the UK’s electricity came from low carbon sources, approximately twice that of 2010. The UK has the largest installed offshore wind capacity in the world, and homes and commercial buildings have become more efficient in the way they use energy (the average household energy consumption has fallen by 17 per cent since 1990.)

This means the UK has been one of the more successful countries in the developed world in growing the economy while reducing emissions. Since 1990, emissions have been cut by 42 per cent while the economy has grown by two thirds. The UK has reduced emissions faster than any other G7 nation.

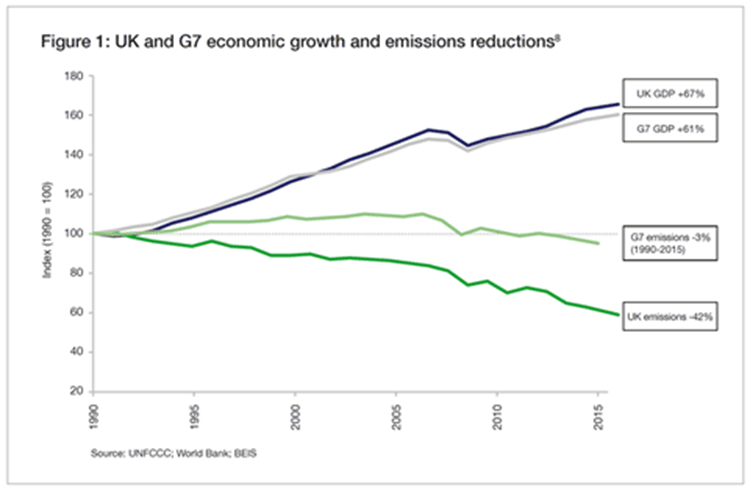

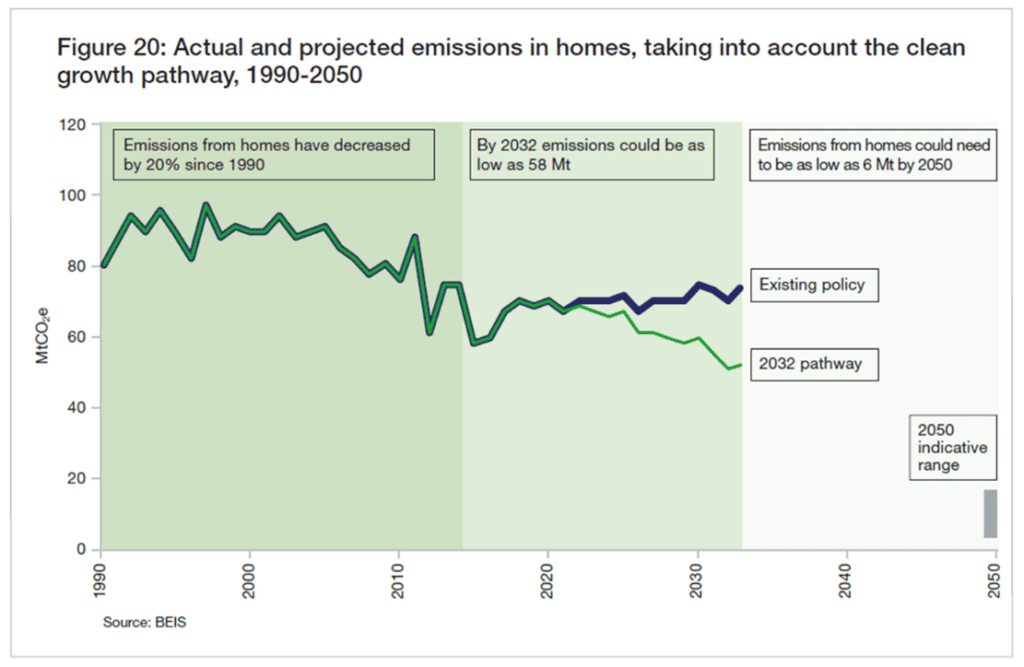

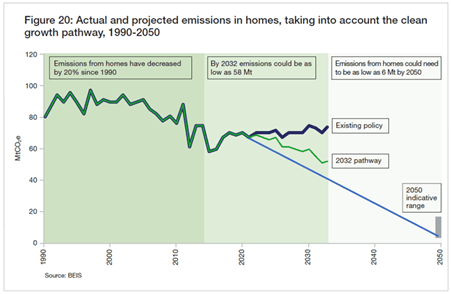

Figure 2: Actual and projected emissions in homes, taking into account the clean growth pathway, 1990-2050

The graph above relates to the carbon output of homes. As you can see, from 1990 to 2020 (another 30-year period), emissions from the energy we use in our homes has fallen by about 20%. This is also reflected in the average SAP rating from UK homes. Back in the mid-90s, the average SAP across all tenures was 46, but it’s now around 62. We have made solid progress.

UK homes play a very significant part in UK overall emissions. Heating and hot water for UK homes make up 25% of the total energy use and 15% of the UK carbon emissions. And a further 4% of carbon emissions are the result of electricity used in the home for appliances and lighting. So, by tackling emissions in our homes, we are contributing to the shift towards zero carbon.

However, this is not to say we can be complacent. As the graph below shows (the blue line is our own addition to the diagram), we have to accelerate progress if we are to hit the 2050 target.

Figure 3: Actual and projected emissions in homes, taking into account the clean growth pathway, 1990-2050

How can we get to Zero Carbon?

If we are to have any hope of hitting the zero-carbon target, then there are two big things we will all have to change: the way we heat our homes and how we travel.

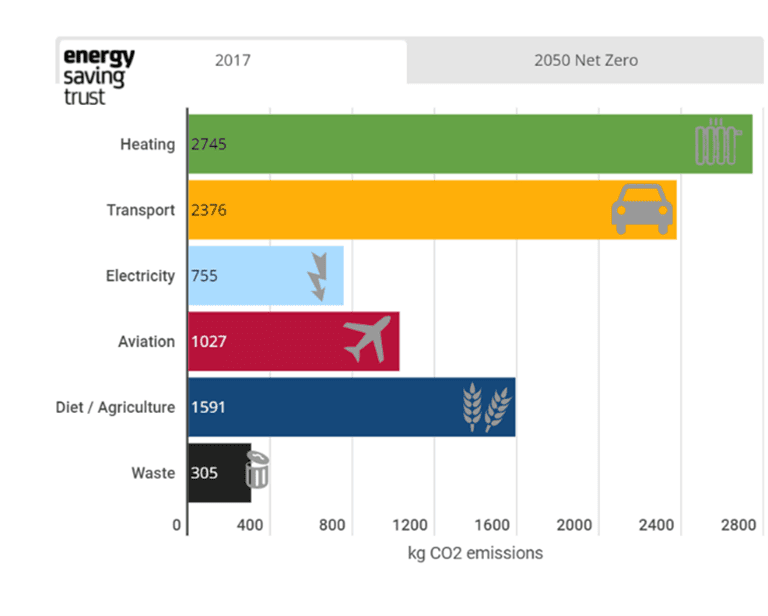

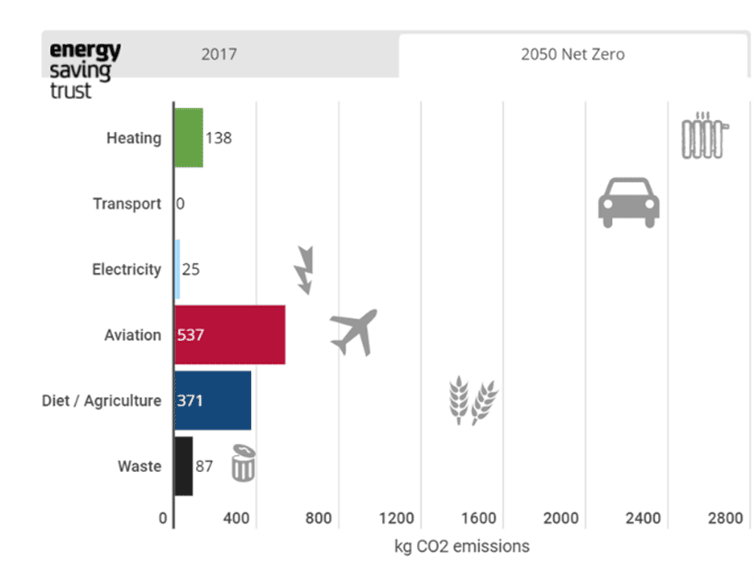

According to the Energy Savings Trust, most household CO2 emissions come from heating (including generating hot water). Energy Catapult Analysis shows that in 2017, the average household generated 2,745 kg of CO2 emissions from heating which is around 31% of the total. To reach the net-zero 2050 target that the UK has now adopted, we need to go even further and reduce heating emissions to 138 kg CO2 per household – a reduction of 95%.

We cannot reduce carbon emissions from heating sufficiently if we continue to use natural gas or oil to heat our homes. This level of reduction requires a substantial shift in heating technologies towards renewable energy. Home renewable heat energy can come from a wide variety of sources: from solar water heating or by extracting the latent heat in the soil, outside air or a nearby water source using a heat pump.

The diagrams below illustrate the scale of the issue.

Figure 4: 2017 UK average household CO2 emissions in kg based on Energy Systems Catapult analysis

Figure 5: UK average household CO2 emissions in kg based on Energy Systems Catapult analysis 2050

What does this all mean for EPCs?

All of the above suggest that EPCs are not going to go away any time soon since there is no other method for measuring the energy efficiency of the UK housing stock.

Possibly in recognition of this, in September 2020, the Departments for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy, and Housing Communities and Local Government published the “EPC Action Plan”. The aims of the plan are to deliver:

- An EPC system that produces accurate, reliable and trusted EPCs;

- An EPC that engages consumers and supports policies to drive action; and

- A data infrastructure fit for the future of EPCs

The plan sets out a preliminary road map for making several changes to the way the EPC is produced, notably a revised RDSAP data set and an investigation to determine if it would be possible to make available the additional information used for calculating EPCS so that property owners (and of course ‘others’) can sense check the EPC. As we shall see when considering the case study later, this will be essential if valuers are expected to realistically consider EPCs when valuing a property.

Improving Home Energy Performance through Lenders – the role of mortgage lenders

In late 2020, the government released a consultation called “Improving home energy performance through lenders”. Feedback is currently being analysed and the government will publish the response in due course, but it seems likely that changes will be coming, and lenders will ultimately play a key role in helping the drive to net-zero carbon. The consultation paper says:

“…mortgage lenders could play a vital role in driving the home energy performance improvements required to meet our Carbon Budgets and net zero target. They are uniquely placed to influence mortgagors at critical trigger points, such as home purchase, renovation or re-mortgage.”

Possibly linked to this (and possibly to the earlier requirement from the banking regulator for financial institutions to show climate change resilience), we believe that at least one major high street lender has recently issued a requirement for its valuers to consider EPCs when assessing the value of property. This is for both the subject property and of the comparable properties considered by the valuer.

What does the EPC tell us?

The EPC is a digital certificate produced using RdSAP (Reduced data Standard Assessment Procedure). Data is fed into a software engine derived from the Government’s national calculation methodology. This enables an energy assessor to generate an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) with a cost-based energy efficiency rating. In other words, the energy rating will be given as a score within a defined scoring band. The bands are between A and G with A being the most energy-efficient and with the lowest fuel bills.

The EPC also provides information about the property on:

- Its environmental impact (CO2 emissions)

- Typical energy/running costs

- Recommendations that can be carried out to improve the property’s energy efficiency, such as loft and wall insulation

For EPCs to be comparable standard assumptions are used in the calculations, and therefore, the EPC is not based on how the actual occupant uses the property or indeed the actual energy efficiency of the property. For example, U-values are assumed based on the date of construction and the insulation measures required by the building regulations in place at the time rather than by accurate calculation of the subject property’s building elements and or services. Domestic Energy Assessors who produce EPCs are also required to follow strict conventions so that the EPCs are standardised and theoretically comparable.

Recommendations for improving the energy efficiency

Recommendations in the EPC are generated through the calculation engine based only on the data input by the energy assessor. The improvements are cumulative, so to reach the potential energy rating, all the recommended measures will need to be installed. If they are installed individually or in a different order, the actual result may differ from the potential result.

How realistic are the recommendations on the EPC?

The recommendations do not consider the actual condition of the property or the suitability of the property for the recommendations made. The energy assessor, the person collecting the data and inputting that data into the calculation engine, is a ‘data collector’. They simply record ‘what is at the property’ – or in other words, they collect the relevant data set. They make no evaluation as to the suitability or otherwise of the recommendations generated for that property. For example, the EPC might make recommendations for solid wall insulation without considering the specific features, defects and or issues at the subject property.

Can we trust the EPC to be a true reflection of the energy performance of a property today?

There are two issues to consider relating to the trustworthiness of the EPC rating:

- Is the EPC current; and

- Is the EPC correct?

Or, to put it another way, how reliable is the EPC?

1. How old is the EPC? – an EPC is valid for 10 years, irrespective of any material changes that might have been carried out to the property since the EPC was created. In other words, it is perfectly legal to market a property with an EPC that is, say, 8½ years old and the property has been substantially refurbished in the meantime. If you go into the government EPC register you can see the date the EPC expires and so, by definition, the date the EPC was generated. But a lot can happen in 10 years.

2. How accurate is the data collected by the energy assessor? – the EPC Action Plan acknowledged that consumers and others need to have confidence in the information on EPCs. However, only 3% of the respondents to the July 2018 “Call for Evidence on Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs)” answered that they believed the reliability of EPCs was good. The government acknowledged in the Action Plan that unless people could trust the EPC, they would not take the rating into account when considering a purchase or acting on the recommendations.

Is this lack of trust down to poor data collection or more a distrust of the EPC in general? 85% of the respondents to the survey thought that the proposal to strengthen the quality assurance processes for EPCs would go some way to improve EPC reliability, and 60% mentioned assessor inputs as a reason for variations in EPC quality. But this might be too simplistic. When the recommendations generated are completely inappropriate, it would be easy to blame poor data input unless you have a clear understanding of the conventions underlying the data input. That said, EPCs are cheap to procure because they are not seen as having any value, so cutting corners in the data collection is understandable.

For example, in attributing for different wall thicknesses the BRE guidance says:

Wall thickness

Measure wall thickness in mm of each external wall (elevation) and any alternative wall within a building part. It can be measured at door or window reveals or by internal/external measurement comparison (which can be direct measurement or estimated by counting bricks). Where thickness varies, obtain a weighted average. For example, a detached house with all side of equal length where the rear wall is 250 mm thick and the remaining walls are 350 mm thick, the average is (0.25 × 250) + (0.75 × 350) = 325 mm.

It would be wrong to assume that an energy assessor never does this because it is not worth their while, but totally understandable if they don’t.

3. Do the conventions give an accurate report on the energy efficiency? – assuming the data input is accurate, how realistic are they anyway? This again comes down to the conventions.

One such is the ‘alternative wall’. The conventions allow for up to 4 different extensions of different ages, but not for different walls of different ages. So, if a Victorian house was altered in the 1980s with a cavity wall, then although that cavity should be built to 1980s insulation standards the EPC conventions would actually assume a Victorian cavity. It is not clear how big an impact this convention has overall since most new walls are likely to be associated with extensions rather than just repairs or alterations. Nevertheless, it does illustrate one of the restrictions on the conventions likely to contribute to inaccurate EPCs.

Finally, it is again worth noting that the SAP methodology itself was not actually designed to assist the drive to zero carbon, but rather as a running cost indicator (as we have already seen), so it will sometimes penalise actions that lower the carbon output of a building (such as installing a heat pump) without sufficiently lowering its running costs. SAP ratings can therefore have a perverse and negative impact on decarbonisation.

The following illustration comes from the Committee on Climate Change, an independent, statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008 with the specific purpose of advising the UK and devolved governments on emissions targets, reporting on the progress being made in the reduction of greenhouse gasses and advising on how to prepare for and adapt to the impacts of climate change. This committee has publicly announced several strategies to help the UK move towards zero carbon, as illustrated here, and few of those strategies or technologies are covered by the EPC.

Figure 6: Committee on Climate Change illustration

EPCs and the approach to valuation

The Green Finance Institute notes in its lender guidance:

“…..accuracy and quality of EPCs is likely to become an increasingly important issue. Future regulations targeting the buying and selling process could give EPCs financial value, which means they will need to be consistently reliable and replicable.” (Green Finance Institute: Lenders Handbook on Green Home Retrofit and Technologies)

As mentioned, one of the ‘Big 6’ high street lenders has already issued guidance that requires the valuer to consider EPCs when undertaking the valuation. They require the following actions for the ‘subject’ property:

- For the valuer to ‘consciously consider’ the EPC rating, and if there is no EPC then to consider the likely rating in relation to other ‘comparable’ stock. (Clearly, for a marketed sale there should be an EPC—unless the property is ‘listed’—but might not be for a revaluation);

- For the valuer to review the EPC certificate and take note of both the work required and the cost of that work to upgrade the property to a C rating and to make reference to the EPC rating and cost of works etc. in relation to the subject property and comparables in the SCT rationale;

- For the valuer to be especially cognisant of older style or ‘non-traditional’ housing where the cost of the improvement works will likely prove inhibitive, and although ‘protected’ to a degree by the cap on expenditure, consideration should be given to the simple fact that their energy performance will be poor in comparison with ‘conventional’ units which may reduce appeal, demand and value.

And for the comparable properties, the valuer should:

- Consciously consider the EPC rating of each comparable

- Take into account that the EPC rating will more likely be a critical factor in relation to price and value at either extreme of the range [“if the subject is an A or B rating then comparables below a D will likely require adjustment (notwithstanding that adjustment would be required in any event to reflect condition and state of modernisation). Conversely the same will apply if valuing an F or G rated property and using A or B rated comparables.”]

- Consider if the property is indeed ‘comparable’ where the ratings are significantly different.

- If there is a wide variation between ratings, “specifically review the EPC certificate of the number one comparable, note what works are required (and the cost) to enable comparison and consider if adjustment is appropriate (either to the comparable or the subject) if not already reflected in price. This will be of particular relevance and importance where the subject property and comparables are below a C rating”

- In each instance, whether adjustment is or isn’t needed (or considered appropriate), the lender expects to see reference to considerations and thought process in the SCT rationale.

It is interesting to note that this lender does not ask the valuer to record the age of the EPC, or indeed, if they have any opinion as to the accuracy of it (for either the subject property or the comparables being considered).

So does the EPC impact value?

“The Green Age”, which describes itself as “the UK’s premier energy saving advice portal, covering heating, insulation and renewable technologies”, wrote a blog post in 2019 stating: “A good EPC can certainly improve how attractive your home is to potential buyers. This is because energy efficiency means lower bills. Studies by both the UK government Department of Energy and Climate Change, and an independent study by My Money Supermarket, have shown how much an EPC can improve the value of a home. In fact, the average English home could increase in value by up to 14%, if improved from a G rating to D.”

Further research quickly reveals a ‘Money Supermarket’ article, probably the same referred to by The Green Age. You can find it here.

There are some heady figures – for example, they make the claim, based on average property values in England, that they can “see a correlation between a stronger energy efficiency rating and a higher house price” and that “raising your EPC from a G rating through to a higher A ratings, where property value can be as much as 14 per cent higher.”

The article also claims that “Homes in the North East see the greatest percentage increase in value, where an improved efficiency rating sees property value increase by 12.2% which equates to £16,219. However, as a result of a higher average property prices the South West sees the highest monetary increase from an improved energy efficiency rating with the average property value increasing by £19,576, an improvement of 7.7 %.”

It is not clear when the post was written (the actual figures will be out of date) but it is the overall picture rather than the detail that is important.

However, what both articles fail to do is consider the correlation between EPC, property condition, and value. A property with an A rating will almost certainly be in better condition and have better amenities than a G rated property.

For example, compare these two houses in MK13.

Property 1 – EPC F https://media.rightmove.co.uk/13k/12663/108093572/12663_9848198_EPC_00_0000.pdf

This is a 3-bedroom property with front and rear gardens. According to the EPC, it is 87m2. It was being marketed following the death of an elderly person. The photographs clearly illustrate the property needs improvement and does not have a modern kitchen or bathroom.

Figure 7: Property 1 front elevation

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

This property is listed on Rightmove at £275,000.

Property 2 – EPC C

https://find-energy-certificate.digital.communities.gov.uk/energy-certificate/2801-3910-1200-0279-6204

This is also a 3-bedroom property, about a 5-minute walk from the first property but does not have a front garden and the rear garden is smaller. The photographs clearly illustrate a modernised property. According to the EPC, it is 100m2.

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

The property was marketed at £290,000.

Property 2 with the better EPC was marketed and we presume sold (at the time of this article, both properties were shown as ‘Under Offer’ on Rightmove) for more than Property 1 with the poorer EPC. But, as the photographs clearly illustrate, to say that Property 2 was worth more because of the EPC is factually incorrect. It is worth more than Property 1 but, factors other than the EPC will come into play.

But what about the Private Rented Sector?

At a recent CPD event, one of the writers asked the surveyors present if they thought EPCs affected value. For the owner-occupied sector, no one thought they did, but for the private rented sector, approximately 40% of the valuers in the room expressed the opinion that EPCs did affect value. This poll was not scientific – it was just a show of hands – so it is far from conclusive; however, it does comprise an example of anecdotal evidence from around 40 Chartered Surveyors who are practising in the real world, carrying out surveys and valuations. Of course, some boundaries between the private-rented and owner-occupied sectors are blurred, meaning that while it is feasible MEES regulations might impact an individual’s decision to proceed with a purchase, that is not the same as saying that MEES impacts the price at which to purchase. Furthermore, MEES might impact value in a slow market, but in the current market where properties are being quickly snapped up, this is less likely to be the case. However, whilst there may currently be no direct evidence regarding any effect EPCs might have on private-rented residential property values, most surveyors are likely to intuitively accept the probability such evidence will eventually be forthcoming. As the minimum rating for let properties is upgraded, and political, legal and financial pressure builds on landlords who are required to spend on improvements to achieve the ‘improved’ ratings, there is likely to be corresponding impacts on values. (If the government were to begin introducing similar ‘carrot and or stick’ policies on owner-occupied properties, similar impacts could result?)

Do surveyors have a role in the drive towards zero carbon?

Surely the answer must be yes.

If the UK is to hit the zero carbon targets, then there is a lot to do and residential surveyors and valuers are well placed to help the UK and the world achieve a positive result. We can raise awareness now by commenting on the EPC, the possible improvement measures and zero-carbon technologies in survey reports. Indeed, the Home Survey Standard addresses this directly:

Section 4.7 Energy matters

Concerns over climate change and legislative and commercial changes in the energy sector have created a demand for clear and objective guidance on energy matters. Consequently, energy advice will be of great value to many clients. We will definitely have a role to play as other lenders start to take account of the EPC. The nature of this service will be influenced by a range of factors that may change over time, for example, global, regional and national legislation and practice; the nature of the subject property and the competence and technical knowledge of the RICS member or RICS regulated firm.

At all levels of service RICS members and regulated firms must be able to identify and advise on defects and deficiencies caused by inappropriate energy efficiency measures implemented at the subject property. In addition, the different levels should include the following particular features:

• Level 1 – where the EPC has not been made available by others, the RICS member should obtain the most recent certificate from the appropriate central registry where practicable. The relevant energy and environmental rating should be reviewed and stated.

• Level 2 – in addition to that described for level 1, checks should be made for any obvious discrepancies between the EPC and the subject property, and the implications explained to the client.

• Level 3 – in addition to that described for levels 1 and 2, at this level the RICS member should give advice on the appropriateness of any energy improvements recommended by the EPC.

Conclusions

There is currently no statistical evidence confirming EPCs impact on value, but it is very likely that they will, either by consumer recognition driven by rising fuel prices or by lender policy as government and the banking regulator enforce legislation arising from climate change policies.

If we agree that the EPC rating is not yet impacting on value, we still need to start thinking about them, and energy and carbon in general; and given all of the above, it is useful to start thinking about them in the context of value. We suggest a simple practice to start employing would be:

- The valuation rationale should reflect and confirm that the EPC has been considered in the inspection and review of the property (as required by the Red Book);

- Note if the EPC is ‘current’ or not;

- Note that the recommended improvements might be only partially realistic (where the EPC is current);

- Note the upper band according to the EPC and the costs suggested in the EPC to achieve the rating; and

- Confirm that this does not impact (yet!) on value.