EPCs and Home Surveys.

In this article, residential surveyor and domestic energy assessor, Tim Kenny, considers the introduction of the RICS Home Survey Standard and the advice surveyors can give to clients in their home surveys in relation to the EPC.

Many years ago, I qualified as a domestic energy assessor (DEA) and produced some of the first energy performance certificates (EPCs) for the then compulsory Home Information Packs. When I started to develop my own reporting practices and templates for home surveys, it seemed obvious to include some information about the EPC in my reports.

EPCs and the Home Survey Standard

With the introduction of the mandatory RICS Home Survey Standard (Professional Statement), which came into effect on 1 March 2021, RICS members and regulated firms must include a commentary on energy matters in all levels of reporting (see section 4.7).

At level 1, if the EPC has not been made available by others, then the RICS member should obtain the most recent certificate from the appropriate central registry where practicable. The relevant energy and environmental rating should be reviewed and stated. This is the case at level 2 as well, when checks should also be made for any obvious discrepancies between the EPC and the subject property, and the implications explained to the client. At level 3, requirements for the lower levels again apply, and the RICS member should also advise on the appropriateness of any energy improvements recommended in the EPC.

The requirement at level 1 simply involves restating factual information; however, the requirements for level 2 and 3 reports are more substantial, with guidance given within the Home Survey Standard and report templates. In this article, I want to share some of my thoughts and experience to help other surveyors meet these requirements in a way that adds value for clients.

The role of the EPC

In this context, it is worth considering the nature of EPCs and their purpose.

EPCs were introduced in 2007 as the UK’s response to the EU’s legislative framework to achieve its energy and environmental goals. The EU recognised that to address energy use and environmental goals, it was essential to address the energy usage in the built environment, and so the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive was introduced. The UK’s response was the legislation that introduced the EPC.

EPCs for domestic properties have two outputs:

- an energy efficiency rating based on estimated fuel costs and

- an environmental impact rating based on CO2 emissions.

Both measures are estimated from the characteristics of the property. The numerical ratings are then banded from A to G, with A being the most energy efficient and G the least. In general, the higher the EER or EIR rating, the lower the fuel bills and CO2 emissions are likely to be. (The A-G banding concept was introduced because of the success of a similar A-G banding on white goods, which had seen a significant shift in consumers choosing to buy more energy-efficient washing machines, for example.)

The legislation requires that an EPC is made available when a domestic dwelling is offered for sale or to rent. However, an EPC is valid for 10 years, and there is no requirement for the EPC available to be current and provide an up-to-date reflection of the energy efficiency of the property when it is marketed. To put it another way, an EPC could be 9 ½ years old when a property is offered for sale or to rent, and in the intervening years significant alterations could have been made to the property.

Domestic EPCs intend to provide the consumer with a guide to the relative energy efficiency of a property.

They are not designed to provide a comprehensive, accurate breakdown of the way a property will perform or the actual running costs. Instead, the software used to generate the EPC makes some standard assumptions about the performance of the fabric of the building and the way it will be occupied. Although limited, EPCs do enable consumers to make some form of comparison between properties based on their likely energy use.

The other key facts to understand about EPCs are:

- the way the data is collected (the conventions that accredited energy assessors must adhere to). For the assessments to be comparable the interpretation of what is on site must also be consistent, so the conventions provide a mandatory framework for the collection and interpretation of what is on site

- the actual EPC can only be generated via a BRE-approved calculation engine.

The calculation engine will assume a standard occupancy based on the size of the dwelling to determine the number of occupants and therefore the hot water requirement. Similarly, it will assume a standard heating pattern based on the volume of the dwelling and following standard heating patterns of nine-hour heating a day during the week and sixteen hours a day at the weekend. These assumptions may not reflect the ‘actual’ way a building is occupied but again, are justified so that meaningful comparisons between buildings can be made.

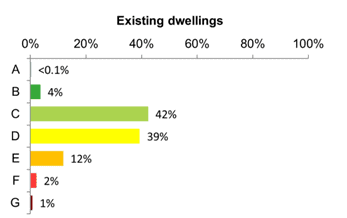

In many ways, this is not ideal but given the variable nature of buildings, they are perhaps the best that can be offered. The most appropriate comparison is with the ranges given for electric vehicles – we all know they will not actually cover the distances stated in the manufacturer’s glossy brochure, but because they are all tested to the same standard, we know a Smart will not travel as far as a Tesla on one charge, even if the comparative difference might vary depending on how the cars are driven. In much the same way, a buyer should be able to pick up an EPC and know that a property rated A should be cheaper to heat than one rated G. However, most properties will not be A-rated but instead will be a C or D.

Figure 1: Energy efficiency ratings (EER): existing domestic properties, England, April to June 2022

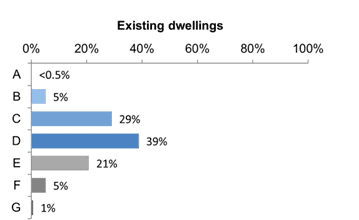

Figure 2: Environmental impact ratings (EIR): existing domestic properties, England, April to June 2022

Recommendations

An EPC itself includes recommendations generated by the software, which, in theory, improve the energy efficiency of the subject property. These recommendations are generated based on the data entry. For example, adding a thermal jacket to a hot water tank will only be recommended where the DEA has identified that an unlagged tank is present. With that said, the recommendations are not totally sophisticated, and DEAs are not trained to recognise ‘show stoppers’ – something that might prevent a recommendation from being carried out – or if they are (because they are also residential surveyors, for example), they simply cannot override the recommendations or add additional data fields to cover condition or legal constraints. In any event, there is no capacity in the software to capture the latter.

The recommendation must increase the EPC rating by at least 1 point (or 0.5 points for low-energy lighting) and the EPC gives an indicative cost and typical savings for the property, calculated by the approved RdSAP engine.

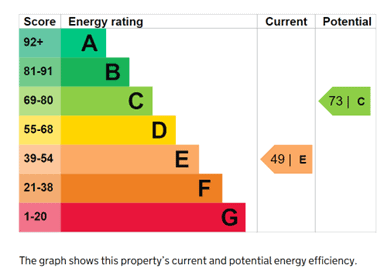

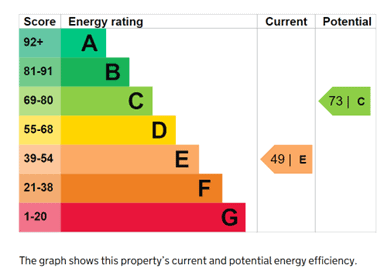

The EPC shows the current and potential energy efficiency. The potential energy efficiency is calculated by the software, assuming that a recommendation will increase the EPC rating by at least 1 SAP point and in a given order.

In some cases, the DEA can suppress recommendations, but only if there is documentary evidence showing that a specific recommendation is not appropriate. So, if a surveyor, who also happens to be an accredited DEA, were to judge that retrofitting cavity wall insulation would be inappropriate they cannot suppress that recommendation.

It is perhaps for this reason – the fact that there are published EPCs with completely impractical recommendations – that EPCs have had bad press in certain quarters.

The role of the surveyor

The Home Survey Standard requires the surveyor to help the client make better use of the broad information and guidance given in the EPC. This creates an opportunity for surveyors. For a level 2 and 3 survey, the surveyor should identify any obvious discrepancies.

A surveyor should identify how up-to-date an EPC is and advise whether or not there have been changes since it was created that may have impacted the rating. Most surveyors provide seller questionnaires to ask the seller about the property. Does the questionnaire prompt the seller to provide information about changes they have made that might impact the EPC? For instance, have they installed another boiler since the original EPC was created?

Identifying discrepancies does not mean that the surveyor should aim to audit the DEA. The surveyor should not attempt to recreate the measurement methodology of a DEA, but instead should note whether there is a significant discrepancy between their own measurement of the floor area or that provided by the agent and the one the DEA has provided. An error in floor area calculation can affect the energy rating since the software assumes occupancy based on the floor area. Comparing the two measurements can also be useful to identify whether the EPC has been produced before or after any major alterations or extensions to the property. Don’t forget that how a DEA is required to calculate a floor area may be very different from the method a surveyor might use, so some difference should be expected. For example, garages, utility rooms, and porches may not be included in the floor area if they are not heated via the main heating system.

The surveyor should always flag any errors in the DEA’s identification of the construction type. Occasionally, these are not in fact errors, but a result of the limited options available when certifying energy use.

For instance, while most houses represent a small range of standard construction types, there are some that do not, such as historic, system build, or unique constructions. A surveyor with specialist knowledge may understand the energy performance of these structures, whereas the software used to produce EPCs does not. Instead, the DEA is obliged to include the property in the closest category available. In such cases, the surveyor should use their specialist knowledge and experience to help their client better understand the energy performance of a property. This is particularly key when considering older solid-walled properties, the data used to generate EPCs has assumed that they have a very poor thermal efficiency when actually, there are some good indicators that many older construction types perform much better than expected.

Another key issue to consider is the insulation in the property. EPCs are often generated using assumptions about the level of insulation, which are made without the full input of a DEA; instead, they are based on factors such as age and construction type. An inspection carried out by a surveyor will often provide more information about the true level of insulation in a property, and this should be conveyed to the client.

A good example is loft insulation. A surveyor is likely to spend more time in a roof space than a DEA, and is not required to follow RdSAP conventions, so they may find evidence of insulation which may be omitted from the EPC. For example, if the loft is fully boarded, the DEA must enter the insulation as ‘unknown’. This will suppress a recommendation, and depending on the age, may assume no insulation is present. However, if a surveyor can see between the boards that there is in fact insulation present, they can advise the client of this and explain that removing the boards and increasing the loft insulation would improve the energy efficiency.

Given this is one of the most cost-effective ways of improving energy efficiency in homes it is important that surveyors bring it to the attention of clients who might otherwise not have thought about it.

Insulation is also a key factor when considering the level 3 requirements. As retrofitting insulation to a property can be a cost-effective way to improve the energy efficiency, this often features among the recommendations made in an EPC. As I have already said, it should be noted that the recommendations within the report are automatically generated with very little scope for altering or suppressing them. It is, therefore, vital that the surveyor reviews these recommendations to ensure they are actually suitable for the property.

A classic example is cavity wall insulation. For some properties, this can be a definite benefit, but for many where a level 3 survey is likely to be instructed, it may be completely unsuitable such as in early cavity wall construction where the wall’s external face may not be watertight, or in an exposed location etc.

It may also be the case that there are defects that would render a recommendation ineffective or even detrimental. Examples may include worn pointing to an exposed wall, or issues with a roof structure that may make it unsuitable for PV panel installation. Where this is the case, the surveyor should always cross-reference relevant sections within the report.

It is also true than many level 3 surveys will be instructed for older or listed buildings where recommendations such as external solid wall insulation or insulation under a suspended timber floor may be completely inappropriate. Here, it is vital that the surveyor advise not only that the recommendation is inappropriate but also why, and detail the potential for harm to the property. Such advice may not take the place of a specialist report on energy efficiency related matters, but it could help a landlord client when considering issues such as the minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES).

The last way I look to add value to my surveys around the EPC is by linking any recommendations within the EPC to specific defects or repair works required at the property. We often think about the recommendations that cannot go ahead because of defects, but there are also some positive aspects. This could include highlighting that the works to resolve an issue you have identified with a solid floor could also provide an ideal opportunity to insulate the floor. The cost of insulating the floor may not be economic by itself but may make sense as part of the larger works required. Another example is removing a textured coating ceiling to a loft room; this is a good time to check and, if applicable, improve the level of insulation.

Conclusion

As Surveyors, we do have to be mindful of liability, and it is important that we consider this aspect when reviewing changes to standards, but that does not mean we can’t also look for opportunities to increase the value of what we offer to our clients. With increased energy prices and the move to carbon reduction, we can take a leading role in helping our clients.

A version of this article was originally published in the RICS Property Journal, however, this version has been extended.