Japanese Knotweed – Where Are We Now?.

Japanese knotweed has a demonstrable impact on the built environment and the native ecology and environment of the UK. Following the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee report, this article takes stock of where we are and how our approach to knotweed may change in the future.

Perception and Reality

Few invasive species capture the attention of the general public in the way that Japanese knotweed has in the UK. Public perception of the issue is not improved by hysterical headlines such as ‘The dreaded alien eating your garden and home… but don’t dare try to kill the Japanese knotweed’[1] on the one hand, and contrarian declarations on the other, ‘Is Japanese knotweed driving you wild? Don’t curse it – cook it’[2].

The truth lies somewhere in between these polarised positions. Japanese knotweed has demonstrable (Figures 1 and 2), though it can be argued, somewhat overstated impacts on the built environment[3] and knotweeds have well-proven negative impacts on UK native ecology and the environment.[4] [5]Eating is certainly not recommended as a control method as the plant accumulates heavy metals and may have been treated with herbicide (rendering it toxic); further, it won’t actually control the plant as invasive knotweeds possess an extensive rhizome (root) system that will take decades of hard work (and knotweed crumbles!) to deplete of resources.

Figure 1: Japanese knotweed causing superficial damage to a wall in Cardiff. In this case, it was likely that contaminated soil was included in the mortar.

© Daniel Jones 2019

Figure 2: Japanese knotweed rhizome (root) growth causing the collapse of a section of wall in Stranraer (courtesy of Brian Taylor).

© The Knotweed Company 2019

While it is easy to highlight misconceptions and deliberate distortion of the issues within the news media, Japanese knotweed is a complex topic that crosses many different fields of expertise, ranging from ecology, herbicide chemistry and civil engineering through to the property and legal sectors.

Biology

In the UK, invasive knotweeds spread principally by the movement of the rhizomes (root material). Rhizomes are modified stems which run underground. They strike new roots down into the soil, but they also shoot new stems up to the surface. This characteristic of rhizomes represents a form of plant reproduction. The rhizomes are also very efficient plant larders, in effect long term energy and nutrient stores. As seed does not germinate in our relatively mild and wet winters, it is rhizomes that cause the plant to spread and it only needs a small section of the rhizome for new growth to be successful.

Because of this method of reproduction, rivers and people are the main means by which the plant spreads. The knotweed rhizome is transported, either unintentionally or occasionally maliciously, via watercourses or in soil. In addition, it has been discovered that in some circumstances, even where herbicide-based control appears to have killed the aboveground parts of the plant, the belowground rhizome is still alive in a dormant state, from which it can still regenerate and regrow if treatment is halted too soon.

For this reason, killing knotweed is not quite so cut and dried. When you kill other plants (such as a tree or a buddleia), when it dies it does not come back. Knotweed on the other hand might just be ‘dormant’ and it is for this reason that we made the statement that managing Japanese knotweed is about long term control and management, not eradication.

Japanese knotweed and property – a potted history

Japanese knotweed has been affecting the UK property market since the 1930s, where it devalued a property in Cornwall to the tune of £100 and earned it the moniker of ‘Hancock’s Curse’. It is worth bearing in mind that this occurred just 50 years after knotweed escaped from cultivation in Maesteg, Wales in 1886.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, legislation was introduced by Government with the intention of slowing the relentless spread of Japanese knotweed. The legislation reflects the biology of the plant. Through the 1990s and 2000s legal restrictions were introduced on the movement and disposal of Japanese knotweed contaminated soil.

However, in our opinion a lack of clarity about how knotweed should be managed using herbicides (and other control and remediation methods) resulted in some lenders overcorrecting on the knotweed issue. Today, lender positions still vary widely from outright refusal where knotweed is present in or near a property, to lending only when a knotweed management plan and insurance-backed-guarantee (IBG) is in place.

In 2012, RICS UK published an information paper entitled ‘Japanese knotweed and residential property’ that introduced a risk assessment framework for Japanese knotweed. This pragmatic framework included a proximity threshold for knotweed growing within seven metres of habitable structures (the ‘7 metre rule’), combined with an appraisal of actual damage to structures. Four risk categories were defined, with the most severe (Category 4) encouraging ‘further investigations’ by qualified surveyors, to ensure that valuation and lending decisions were based on reliable evidence.

Legislation Summary

Japanese knotweed is subject to legislation, some of which is relevant to discussion of the effects in the built environment:

- Japanese knotweed is listed in Schedule 9 of The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981—this legislation makes it an offence to plant Japanese knotweed or cause it to grow in the wild

- However, it is not illegal for Japanese knotweed to be on private land and there is no legal obligation to remove or control knotweed on private land. There is also no requirement to report that Japanese knotweed is present on the land. That said, allowing contaminated soil or plant material from any waste transfer to spread into the wild could lead to a fine of up to £5,000 or a prison term of up to two years. Privately, actions by landowners of adjacent properties seeking damages should Japanese knotweed be allowed to spread onto their property are, of course, well known.

- Japanese knotweed is classed as ‘controlled waste’ so must be disposed of safely at a licensed landfill site in accordance with the Environmental Protection Act (Duty of Care) Regulations 1991. This does not just apply to the plant material above ground. Soil containing the rhizome root material may be regarded as contaminated and, if taken off a site, must be disposed of onsite by encapsulation or deep burial (to a depth of at least 5 metres) or offsite at a suitably licensed landfill site. Section 33 of the Environmental Protection Act states that it is an offence to deposit, treat, keep or dispose of controlled waste without a licence.

It therefore goes without saying that having Japanese knotweed on land carries ‘risk’, hassle and cost.

The House of Commons Science and Technology Committee

Because knotweed is such a complex issue covering legal, property valuation and liability, herbicide chemistry, civil engineering and ecology issues, the problem was acknowledged by Government and in late 2018 a House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Inquiry was launched – ‘Japanese knotweed and the built environment’.

A range of professional and commercial organisations was included in the Committee’s enquiry, including ‘Advanced Invasives’, which was invited to present both written and oral evidence to the enquiry.

The enquiry published its findings in May 2019[6]. It is hoped that the key recommendations of the report, which focus on cross-disciplinary academic and industry research, will help to demystify Japanese knotweed for UK homebuyers and the wider property industry.

The Committee report concluded that:

- Despite the anxiety it can cause householders, latest research suggests that knotweed causes no more ‘damage’ to property than other disruptive plants

- However, it is particularly difficult to eradicate, and effective control requires a multi-season herbicide management programme

- There is a risk that treated plants will regrow

- There is surprisingly little research on the physical effects of knotweed on the built environment

- The Environment Agency should convene a meeting with major knotweed remediation firms to explore how a dataset could be assembled to contribute to this ongoing research

- Mortgage lenders in other countries do not treat the plant with the same degree of caution so Defra should commission a study of international approaches in the context of property sales to inform discussion of this issue

- RICS and the Law Society should consult on a revision of the wording on the Property Information Forms in particular to determine if there is a need to declare previous problems with the plant if the plant has been treated by appropriate excavation and there has been no regrowth within a given period of time

- The RICS risk assessment has enabled lenders to lend on affected properties where there is a treatment plan backed by an insurance guarantee in place

- The RICS 7-meter rule is a bit of a blunt instrument and a more nuanced and evidence-based risk framework is needed and they hoped that this work would be completed before the end of the year

- Government should produce additional guidance on dealing with litigation that results from dispute between landowners due to Japanese knotweed

As we know, the RICS Japanese knotweed risk assessment framework was somewhat overtaken by events unfolding in common law knotweed cases across the UK.[7],[8] While high profile cases such as Williams & Waistell v Network Rail

Infrastructure Ltd. attract headlines in the media, these represent only a subset of those settled out of court. Against this backdrop of growing legal liability, property surveyors have increasingly practiced more defensively. Consequently, the RICS framework which was intended as a descriptive framework to better reassure lenders has become a prescriptive label, whereby lenders may automatically reject loans on properties within 7 metres of a knotweed infestation.

Where does this leave property surveyors?

Following the recent House of Commons enquiry, RICS is now heading the Japanese Knotweed Leaders Forum, to review industry knotweed guidance. However, we believe this remains some way off and even when agreed, it is widely acknowledged that surveyors will still be required to identify knotweed during property surveys. Getting this right is essential for minimising surveyor legal risks in this area.

How do you identify Japanese knotweed during a survey?

Identifying invasive knotweeds in the UK can be problematic for non-specialists. To begin with, there are four different species of knotweed:

- Japanese knotweed

- Dwarf knotweed

- Giant knotweed

- Bohemian knotweed

Though each of the four species share many common features, they are often confused with native UK weeds and garden plants, even by contractors within the knotweed remediation industry. Additionally, the appearance of invasive knotweeds changes through the year – particularly in the winter months, when the leaves have fallen and all that remains is the dry, dead stems (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Japanese knotweed growing along the banks of the River Taff in Cardiff; (A) in the summer and (B) during winter, following die-back.

© Daniel Jones 2019

Identification of invasive knotweeds is tricky at the best of times. This is made more difficult as many property vendors are aware that at the present time divulging the presence of knotweed on their property[9] could reduce its marketability and sale value. Consequently, knotweed may be intentionally disguised (indeed Sava has investigated several claims against surveyors where this has evidently been the case). Figure 4 highlights two examples of this in Southampton and Bristol, respectively. In both cases, concrete has been used to unsuccessfully cover knotweed growth – at Advanced Invasives we know of examples of bark chip, gravel and plastic coverings also being used for this purpose.

Figure 4: Japanese knotweed growth from unsealed gaps in laid concrete; (A) Southampton and (B) Bristol.

© Daniel Jones 2019

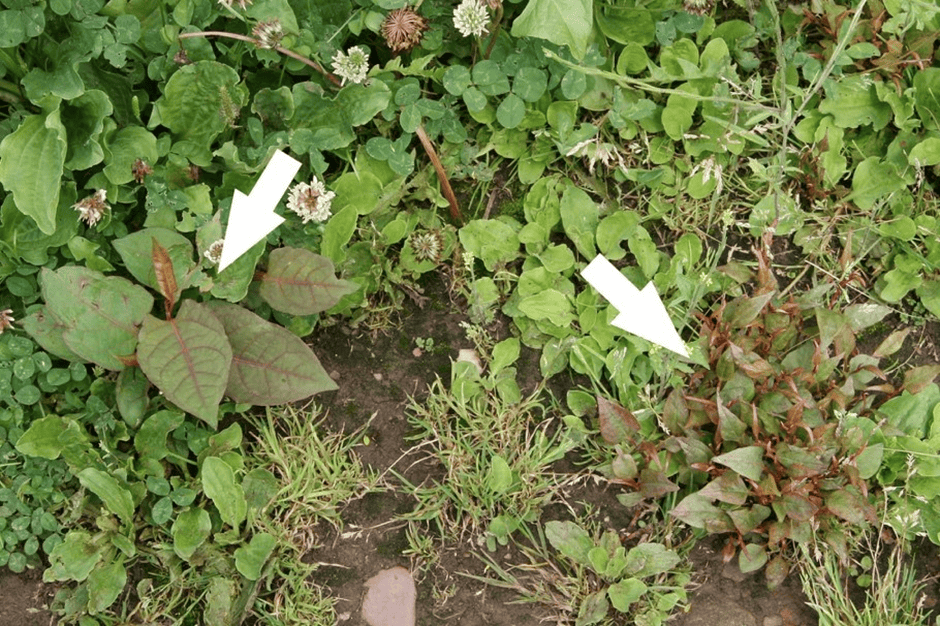

To complicate identification further, invasive knotweeds look very different following herbicide application, even if this has been successful. Figure 5 highlights two very different growth forms of Japanese knotweed following treatment with glyphosate-based herbicide. These growth forms are not only difficult to identify but are also low growing and often obscured by growth of other vegetation, making spotting them difficult.

Figure 5: Two different deformed Japanese knotweed growth forms following treatment with glyphosate-based herbicide in Cardiff. Would you spot these?

© Daniel Jones 2019

Next Steps

We look forward to receiving the revised industry guidance from RICS but in the meantime Advanced Invasives is exploring with Sava a series of professional development courses and training content leading to smaller competency based qualifications designed to assist surveyors with the identification, survey and appraisal of invasive knotweeds in the property context.

About Dr Dan Jones

PhD, MSc, BSc, GCIEEM

Dan Jones is the Managing Director of Advanced Invasives and also an Honorary Researcher at Swansea University, with over ten years’ experience across the ecological sector. He founded Advanced Invasives to bring evidence-led thinking to the forefront of the commercial management of invasive plant species and is one the UK’s leading authorities on the strategic control of Japanese knotweed and the ecological dynamics and mechanisms of non-native plant invasion.

At Advanced Invasives, Dan leads the development of in-house best practice for the management of Japanese knotweed across large infrastructure and heads up the novel research into herbicide effectiveness and sustainable use. He is chief expert witness and a sought-after speaker on Japanese knotweed ecology.

[1] Derbyshire, D (2013). Mail Online. Available from: https://dailym.ai/2YKjUlw [Accessed 26/01/18]

[2] Sanderson, D quoting Fowler, A (2018). The Times. Available from: https://bit.ly/2YCTEt4 [Accessed 30/05/18].

[3] Fennell M, Wade M & Bacon KL (2018) Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica): an analysis of capacity to cause structural damage (compared to other plants) and typical rhizome extension. PeerJ 6:e5246; DOI 10.7717/peerj.5246.

[4] Dawson, FH & Holland, D (1999). The distribution in bankside habitats of three invasive plants in the U.K. in relation to the development of control strategies. Hydrobiologica 415: 193-201.

[5] Bailey, JP, Bímová, K & Mandak, B (2009). Asexual spread versus sexual reproduction and evolution in Japanese Knotweed s.l. sets the stage for the ’‘Battle of the Clones”. Biological Invasions 11: 1189-1203.

[6] House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Inquiry: Japanese knotweed and the built environment (2019). Available from: https://bit.ly/2vZIUsF) [Accessed 16/05/19].

[7] Clargo, J. (2018). Japanese knotweed nuisance in the light of Waistell and Smith v Line. Available from: https://bit.ly/2M3go42 [Accessed 11/11/15].

[8] Creer, A. (2018). Oh, that Knotweed! Sorry, didn’t I mention it?. Available from: ttps://bit.ly/2WfqRxp [Accessed 11/11/15].

[9] The Law Society TA6 property information form and LPE1 leasehold property enquiries form.