Permitted Development Rights.

There are certain types of development work when planning consent is deemed to have been granted by Government, as opposed to by a local authority on a case by case basis. These are called “permitted development rights”. In this article, Chris Pipe from Planning House explains the basics of permitted development rights and use classes and considers some of the conditions and limitations that may apply for various developments.

These conditions and limitations can vary depending on location and the nature of the proposed development.

The article also considers where a Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) may still be applicable, even if a development does not actually need planning permission.

Planning Consent

Over the last 100 years, a detailed system of local and central control over what can be built and where has evolved. The need for planning grew out of industrialisation, the development of towns and cities following mass migration from the countryside and the public health issues that resulted. While some of the legislation to address this is more commonly associated with the development of building control, some early planning legislation emerged. For example:

- Town Planning Act 1909 – this banned the building of ‘back-to-back’ housing, symbolic of the poverty and poor housing of the industrial cities. It also allowed local authorities to prepare schemes of town planning

- Housing Act 1919 – part of the raft of legislation following the First World War to address the ‘homes fit for heroes’ initiative, this gave the Ministry of Health authority to approve the design of houses

- Housing Act 1930 – this required all slum housing to be cleared in designated improvement areas

Planning law continued to develop and is now enshrined in a series of key statutes supplemented by rafts of central guidance in the form of planning policy statements.

The principle of planning law is that it requires the owner of a property to seek permission before a building is constructed, substantially altered or the use of the property is materially changed. Parliament has given the main responsibility for planning to local planning authorities (usually, this is the planning department of the local council) and planning permission will be granted (possibly subject to certain conditions) or refused.

There are exceptions to this, namely:

- Exempted activities – this is a list of activities that have been determined not to constitute development. An example will be changes of use but within the same class of the Use Class Order e.g. the change of one type of office to another type of office

- Permitted development – cases where no express consent is required from the local planning authority. To put it another way, planning consent is already considered to have been automatically granted

This article explores permitted development.

Stay on the safe side

Although permitted development in essence allows for development to proceed without first obtaining specific consent, it is nevertheless always recommended that anyone planning a project should contact the local planning authority to establish if the development will be permitted or if planning permission is needed. Local authorities have certain powers enabling them to overrule the basic principle of permitted development and the risk of going ahead with works without contacting the council could result in an unauthorised development and lead to enforcement action.

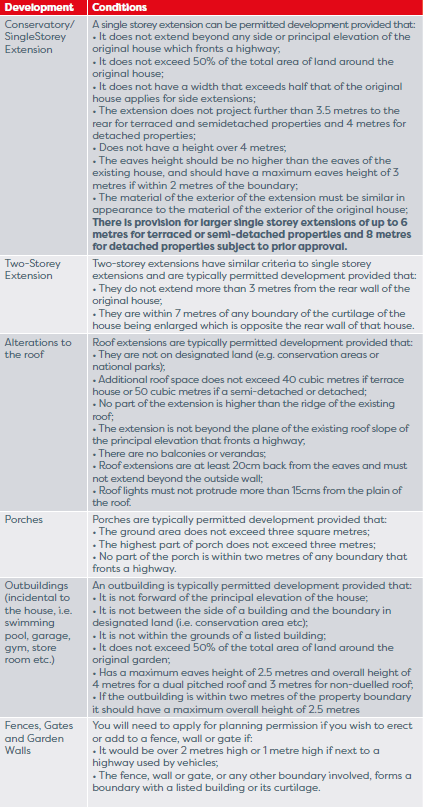

Knowing all the various conditions that may apply can be tricky, but the below table lists common developments and the conditions that apply. This should be read in conjunction with the relevant legislation which can be found at www.legislation.gov.uk

Removal of permitted development rights

One mechanism by which the local planning authority can remove permitted development rights is by issuing an ‘Article 4’ direction. This means that planning permission will need to be submitted, even though the work would not normally require it.

An Article 4 direction is made when the character of an area of acknowledged importance would be threatened. This is likely to occur in conservation areas.

Check for conditions

Planning permissions in themselves can remove permitted development rights that might normally follow through the imposition of a condition on an approval. For instance, on new housing estates where gardens may be limited, permitted development rights may be removed for extensions, conservatories etc.

If an Article 4 direction is in place or a condition restricts development, it does not mean the project will not progress; it just means planning permission is required via the planning application process.

Fast-track conversions

Have you ever looked at a barn or building in the countryside and thought ‘that would make an amazing home’, then thought about the hoops you would have to jump through to secure permission to convert it? Well, it may be that those obstacles are not quite so onerous.

In some instances, planning permission isn’t required to convert a building into residential use. Under Part 3 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015, GPDO for short, there are a magnitude of uses (retail, launderette, betting shop, shop, offices, amusement arcade, casino, storage or distribution centres, agricultural buildings, etc.) which can be converted to residential as ‘Permitted Development’ without planning permission.

There are, however, a range of exclusions and limitations which apply, and each use proposed to be changed has a different set of conditions which must be adhered to, such as type and location of land/buildings, date of last use, amount of floorspace and/or information which must be submitted and considered by the local planning authority prior to any change of use.

The ‘green light’ given to convert specific uses to residential has seen an increase in the growth of conversions, particularly agricultural buildings in the countryside. With the Government encouraging the creation of more housing, permitted development rights have recently been increased.

PDRs now allow a maximum of 5 new houses to be created from existing agricultural buildings on a farm. Previously this was restricted to 3 properties.

The amendments which came into force in April 2018 permit the development of:

- up to three larger homes within a maximum of 465 square metres; or

- up to five smaller homes each no larger than 100 square metres; or

- a mix of both, within a total of no more than five homes, of which no more than three may be larger homes.

If it’s thought that an agricultural development may be permitted, the planning authority should still be contacted and a prior approval process will be required. This is where a developer seeks approval from the local planning authority that specifies elements of the development are acceptable before work can proceed – in effect, a ‘light-touch’ planning application.

As well as the potential to create a dream home in the countryside (or maximise land and development value), there are many ways to circumvent the need for planning permission for extensions, alterations, change of use, temporary buildings and uses etc. However, interpreting the regulations which set out what can and can’t be done via permitted development rights can be daunting so expert planning advice is suggested for anyone considering such a scheme.

Prior approval process

Before beginning a project, prior approval may be required from the local planning authority. Whilst planning permission isn’t required for certain developments, prior approval may be. This is dependent on what is being built and is explained in detail in Schedule 2 to the General Permitted Development Order.

The prior approval process is a ‘lighter touch’ process than a planning application and it can only be used BEFORE works begin. If works have already started, then it is not possible to take advantage of the simplified process.

Prior approval timescale

When a local planning authority receives an application for prior approval, they have 56 days to make a decision as to whether approval is needed and, if so, given.

If the local planning authority does not notify the applicant of their decision within the 56 days and IMPORTANTLY the proposal meets the criteria within the General Permitted Development Order regulations, the applicant can go ahead with the development.

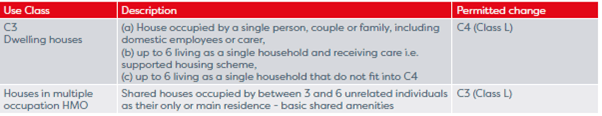

Use Class Order

The Use Class Order (Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order 1987) (as amended), categorises uses of lands and buildings. To change the use of a building may require planning

permission, however, there are permitted changes of use that can be made without planning permission, under Part 3 of the General Permitted Development Order. For the purposes of this article, we have just included permitted changes for dwellings and HMOs, as well as agricultural buildings:

In addition to the above, agricultural buildings are permitted to be changed to a residential dwelling subject to prior approval (Class Q). Also, there are permitted flexible changes as those listed below:

Class A – restaurants, cafes, or takeaways to retail

Class B – takeaways to restaurants and cafes

Class C – retail, betting office or pay day loan shop or casino to restaurant or café

Class D – shops to financial and professional

Class E – financial and professional or betting office or pay day loan shop to shops

Class F – betting offices or pay day loan shops to financial and professional

Class G – retail or betting office or pay day loan shop to mixed use

Class H – mixed use to retail

Class I – industrial and general business conversions

Class J – retail or betting office or pay day loan shop to assembly and leisure

Class JA – retail, takeaway, betting office, pay day loan shop, and launderette uses to offices

Class K – casinos to assembly and leisure

Class M – retail, takeaways and specified sui generis uses to dwellinghouses

Class N – specified sui generis uses (amusement arcade/centre or casino) to dwellinghouses

Class O – offices to dwellinghouses

Class P – storage or distribution centre to dwellinghouses

Class PA – premises in light industrial use to dwellinghouses

Class R – agricultural buildings to a flexible commercial use

Class S – agricultural buildings to state-funded school or registered nursery

Class T – business, hotels etc to state-funded schools or registered nursery

The above are all subject to the prior approval process.

BE AWARE: Even if your development does not need planning permission, you still may be liable to pay a Community Infrastructure Levy, or CIL as it’s commonly known. CIL is a tool that allows local authorities to collect a ‘tax’ style payment for developments. CIL is non-negotiable once it’s adopted by a local planning authority, with rates set out in a Charging Schedule, generally published on a Council’s website. You can read more about this in one of our Planning House eBooks which you can download for free on our website www.planninghouse.co.uk

Summary

Permitted development rights and Use Class Order are a complex part of the planning process. If you consider there to be scope, under the provisions identified above, for development, seek assistance from a town planner to confirm the position.

Chris Pipe

Chris has a wealth of experience in the town planning industry and, as former Head of Planning for a Council, working as UK Planning & Land Director for a large PLC and by launching Planning House in 2016, she knows her way through the planning system from a unique perspective, which is why the label ‘Gamekeeper turned Poacher’ has never been more appropriate. Chris is also a non-salaried Planning Inspector, working for the Planning Inspectorate determining appeals refused by local planning authorities.