Fire Risk Assessment and The Residential Practitioner.

An article by Phil Parnham (Bluebox Partners) and Richard Twine (Regulation Solutions)

1.0 Introduction

The fire at Grenfell Towers is a national disaster. Until all the investigations and enquiries have finished and their findings reported, there is no useful contribution we can make apart from holding those whom have suffered in our thoughts at this difficult time.

Although these are early days, it seems likely these terrible events will result in a radical overhaul and change in the fire regulations and associated legislation. The Government have announced they will be reviewing the building regulations. We do not know the scope or the timescale but it is clear that fire regulations will be very different when the dust settles.

However, because it is going to be many months, if not years, before this occurs there is going to be a period of uncertainty. Lenders will be unsure of the risk in this type of lending and they will have worries about how uncertainty will affect the value of their ‘back-book’. During this time, surveyors and valuers who made numerous assumptions about the safety and security of high rise buildings will be concerned these have now been undermined. Consequently, it will be some time before the market reflects what public opinion thinks about the safety and security of not only buying but also renting high rise property.

RICS has been sending out useful email updates containing links to advice and guidance from the Department of Communities and Local Government and other authoritative organisations. While these are important contextual documents, they do not give guidance that would be of use to valuers at the coal face.

Consequently, residential practitioners are left in a familiar position: facing a complex issue with little practical help but still expected to decide on whether a property meets the varying criteria of different lenders. It is no surprise that inconsistent valuation decisions will be the result.

This article attempts to give residential practitioners usable information about the assessment of flats that form part of large, purpose-built blocks. This information is not new. It makes no attempt at second guessing how future regulations may change and neither does it take account of stopgap lender guidance. Instead it concentrates on the processes and regulations as they stood before this tragedy occurred.

This article is not only about flats. Government statistics show that there were 303 fire-related fatalities in 2015/2016 and 80% of these were in the home. This is a 15% increase on the 2014/2015 which itself was a 25% increase on the previous year. Even without Grenfell Tower, this was already a shocking situation. Consequently, this article also looks at low rise dwellings but houses in multiple occupation (HMOs) will not be included due to their particular complexity. We intend to cover these in a future bulletin. ‘Sheltered’ or ‘Assisted Living’ accommodation has additional requirements which are not covered here.

2.0 Assessing residential properties for compliance

Most of the Residential Surveyors we know are not ‘fire experts’ and are not qualified to carry out or check fire risk assessments. This is because most are not Fire Engineers and cannot evaluate alternative or novel fire prevention solutions.

However, we think any reasonable residential practitioner should have a broad awareness of related matters, be familiar with the key benchmarks that govern this area and be able to recognise the most obvious ‘trails of suspicion’ that may suggest non-compliance.

Important Note: in this article, we have summarised some of what we think are the most important indicators of whether the means of escape and other safety provisions in a property are likely to be acceptable. For reasons of brevity, we have not included all the detailed provisions of these complex regulations. Consequently, it is your responsibility to make sure your day to day practice is compliant. You can do this by downloading and reading the benchmark documents listed below. Not only will that give you a better understanding of the topic area but we think it can be logged against your informal CPD targets.

2.1 The key benchmarks

We think the reasonable surveyor should be aware of and have access to the following publications:

The key document for flats is:

- ‘Fire Safety in purpose-built blocks of flats’ published by the Local Government Association in May 2012 and this can be downloaded from https://www.local.gov.uk/fire-safety-purposebuilt- flats for free.

Additional documents of use are:

- Building Regulations Approved Document B, volume 1 (Dwellinghouses) and volume 2 (contains guidance on flats)

- The LACORS guide to Housing Fire Safety

- HM Government guide Fire Safety Risk Assessment & Sleeping Accommodation

2.2 Fire safety – some general principles

Before we get into the detail it will be useful to focus on some fundamental concepts that form the building blocks of fire safety.

2.2.1 Fire doors

A fire door is one that has been tested to show it achieves resistance to the passage of fire and smoke for a certain period of time. Self-closing devices on internal doors have not been required within dwellings under the Building Regulations since 2006 (except internal doors that connect a house to a garage).

Fire doors usually require an intumescent strip to achieve their rating. This appears as a solid, plastic-type strip rebated into the door edge or frame. This strip expands at high temperatures to seal the door to the aperture and protect the most vulnerable part of the assembly from flame. However, it does nothing to stop the passage of cooler smoke in the early stages of a fire, which is why smoke seals (either a brush or rubber blade) are used.

Although smoke seals are sometimes required, some commentators consider there may be disadvantages within dwellings. relies on smoke detectors in the circulation areas then smoke seals on a bedroom door may allow the fire to develop for some time before setting off the alarms. However, flat entrance doors should always feature smoke seals, intumescent strips and self-closing devices.

Note, in older buildings, ‘historic’ doors are often upgraded without changing the panelled outer face, by the use of additional boarding, or the use of intumescent paints or papers. It is difficult to identify whether a panelled door has been upgraded but the following indicators may help:

- When opened and closed, it feels ‘heavier’ than normal doors of that age and type;

- Looking along the edge of the door, you may be able to see where additional layers have been added to the inside face.

- If the original door was thick enough, only the door panels would have been upgraded. In this case, the depth of the rebate (usually) on the inside will be slightly smaller than that on the other side.

2.2.2 Fire escape windows

Windows can only provide an alternative means of escape in dwellings where the floor of the property is less than 4.5 metres above the external ground level. In this case, the window should have a minimum size of 0.33m2 with minimum clear opening dimensions of 450 x 450mm and a maximum 1100mm from floor to bottom of the opening. Although window locks are allowable, any restrictors need an override so they can be fully opened.

2.2.3 Inner rooms

These are rooms where the exit from the room is through another, adjacent room (known as the access room). Typical examples are kitchens, bathrooms, ensuite bathrooms and WCs and so on. Habitable rooms can only be inner rooms if they have a suitable door or escape window that meets the requirements described above. ‘Inner-inner’ rooms are rooms where the exit is through two other rooms. These are only acceptable if additional fire detection is provided and none of the two access rooms are a kitchen.

2.2.4 Fire detection and warning

This is probably the most important fire safety provision in buildings where people sleep. Early warning buys the occupants time – in a dwelling this allows the responsible adults time to gather their family members before exiting the building, hence the provision of fire doors too in taller dwellings. Since 2000, all new dwellings and most extensions should have been fitted with automatic detection and warning. These should be:

- Mains-wired and interlinked with other smoke detectors in the property. They should have a battery backup and meet all other standards laid down in the building regulations

- They should be sited in circulation areas such as corridors and stairs, and on every storey

- Where kitchens are open to the stairs and corridors, heat detectors should be fitted in the kitchen in addition to the smoke detection. This arrangement would only normally be suitable in two storey dwellings where escape via a window is viable.

For houses in multiple occupation, the positioning, type, and grade of detection system are more complicated and will depend on many factors. We will return to HMOs in future articles.

2.3 Means of escape for typical property types

The previous section covers some basic principles but how do these relate to the fire escape provision from dwellings we normally encounter? To help, we have identified some typical property types and the sort of escape provision you should expect.

2.3.1 Bungalows

This is the probably the most straight forward. All habitable rooms should either:

- Open directly into a hall that leads to a suitable exit door; or

- Have an escape window that conforms to that described in section 2.2.2 above. The property should be fitted with a suitable fire detection system (see 2.2.4 above) if built after 2000.

2.3.2 Two storey houses

The ground floor requirements are as described for bungalows in the previous section.

For the first floor, all habitable rooms should have:

- An escape window as described in 2.2.2 as long as the floor level of the upper storey is less than 4.5m off the outside ground level, or;

- Access to a fire protected stair leading to a final exit.

- Again, dwellings constructed post-2000 should be afforded a suitable fire detection system.

2.3.3 Three storey houses

The higher the building, the more complicated the provisions become especially as the regulations have changed a number of times in recent years. You may come across properties that conformed to the regulations at the time of construction/conversion but wouldn’t meet the benchmark today. You will have to come to a professional judgement based on the evidence but the following notes may help:

- Up to 2006, loft conversions had to have escape windows close to the eaves of the roof and self-closers to existing doors in the protected staircase instead of new fire doors. These provisions have now been superseded.

- After 2006, escape windows from the second floor are not an option and all doors opening onto the protected staircase should have a 20 minute fire resistance (FD 20).

- If the ground floor is open plan and the first flight of stairs and route to the final exit are not protected, then there must be:

- A fire door separating the first floor from the open staircase

- An escape window at first floor

- Sprinklers protecting the ground floor

These are the most common scenarios – there are many other variants and if you want more detailed information then please see Approved Document B to the building regulations.

2.3.4 Houses that are four storeys and above

Properties at this height (storeys 7.5m above outside ground level or higher) usually require an alternative means of escape (for example, a second internal or an external stair) or a full sprinkler system. This is a complex regulatory area so asking for clear confirmation that the solutions meet current benchmarks is vital. Properties built prior to the modern regulations (pre-1985) will often not meet this guidance. At the very least the stair should be protected by suitable fire doors and the property be fitted with mains-wired, interlinked smoke detection in the circulation areas at all levels. With the absence of an alternative stair or sprinkler system it would be prudent to cover all risk rooms with interlinked detection.

2.3.5 Basements

A fire in a basement can quickly block a single stairway with smoke. Therefore, for basements that contain a habitable room the property should have:

- A suitable external door or window that allows escape from the basement.

- A protected staircase leading from the basement to a final exit.

- Even where the basement/cellar does not contain a habitable room, additional fire protection and detection may be required.

Like higher dwellings, basements pose additional complications when assessing fire escape standards so you should proceed with caution and put a higher emphasis on obtaining clear evidence of compliance with current benchmarks.

2.4 Obvious signs of non-compliance or ‘follow the trail’.

If what you see on inspection falls below the typical benchmark standards as described above, then a referral for further investigation may be justified. However, as with other aspects of your survey, you will have to make a call on a case by case basis depending on what you can see on the day.

The following indicators may help you decide:

- For dwellings with older windows at ground and first storey – Do they open sufficiently to enable someone to climb out in the event of a fire? Many will not conform to the dimensions laid down in the current regulations. If this is the case, it may be appropriate to warn clients of the higher risk.

- Are smoke alarms present at every level? Even if the answer is yes and the alarms are battery operated, it may be appropriate to warn clients these are not as safe as a hard-wired and interlinked system. If there are battery powered fire alarms, have the batteries been removed? If there are mains wired alarms, is there evidence these have been regularly inspected and tested?

- Have doors that should be fire rated been altered so their fire resistance may be compromised? For example, heavy fire doors taken off or replaced with lighter alternatives.

- Do dwellings with rooms above first floor have an open stair at ground floor? Has the fire separation been removed to make the stair open-plan?

3.0 Flats in purpose provided blocks

The complexity of regulations that govern fire escape in blocks of flats are far more complex than those for houses. Engaging with this level of regulation presents many pitfalls and problems. For example, the common areas of flats and maisonettes are controlled by The Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005. Scotland and Northern Ireland have separate fire service and fire safety legislation: The Fire Safety (Scotland) Regulations 2006 and the Fire Safety Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2010.

The approach taken under this legislation is a ‘risk assessment based regime’ requiring employers, property owners and their managers (amongst others) to take action to prevent fires and protect against death and injury of employees and other relevant persons, including tenants.

Probably the most relevant publication is ‘Fire Safety in purpose-built blocks of flats’ published by the Local Government Association in May 2012 and this can be downloaded from https://www. local.gov.uk/fire-safety-purpose-built-flats for free.

Before we look at any further detail, it will be worthwhile reviewing two general principles: ‘stay put’ strategies and fire risk assessments.

3.1 ‘Stay put’ policies

The Grenfell Tower tragedy and the previous fire at Lakanal House in Southwark has placed the policy of ‘staying put’ at the centre of any forthcoming enquiry. The theory goes something like this: if each flat or compartment has a fire separation of at least one hour then occupants should remain in their homes until the fire is extinguished or unless instructed otherwise by the emergency services. The logic behind this policy is that if all the flats in a block were to be evacuated simultaneously when a fire alarm is triggered, the resulting chaos could makes matters worse. Any alternative to ‘stay put’ would rely on an interlinked alarm system, which raises its own issues. For example:

- Who carries out the weekly fire alarm test, and at what time are the tests? How can a fire alarm engineer access every flat on the same day to perform twice-yearly maintenance? With 129 separate flats in Grenfell Tower for example, the logistics would be challenging to say the least.

- After a few false alarms at 3am, few of the upper floor occupiers are likely to respond to the next alarm.

- What would happen to those who rely on the lifts? Would the elderly and disabled be left stranded?

- There could also be a corridor and/or stairway clash between occupants trying to leave the building and personnel from the emergency services trying to access the building at the same time.

For these reasons, published guidance and most fire risk assessments for blocks have been based on the ‘stay put’ principle. Guidance states that fire alarm systems are only interlinked between residencies and common areas in exceptional circumstances.

Due to the adoption of ‘stay put’ strategies, the fire resistance between flats and to the common areas (compartmentation) is of critical importance. In the case of Grenfell Tower the ‘stay put’ policy was initially effective as the compartmentation held the fire in the flat of origin until it was extinguished. The disastrous failure of the external cladding system is what compromised this policy.

3.2 Fire escape within the flats

Once within the flats, the simplest layout from a fire safety perspective is where all the habitable rooms have access to an internal hallway. In this case, the internal hallway should be protected by fire resisting linings and all internal doors should be 30 minutes fire resisting. However, experience suggests many older flats will not meet this standard. To meet modern standards the flat should also be fitted with hard wired alarms.

There are many other flat configurations (for example, flats with restricted travel distances, flats with open plan areas and those that have more than one storey). The requirements for these types of dwelling can be particularly complex and should be left to the specialists to assess.

3.3 Fire risk assessments (FRAs)

A fire risk assessment (FRA) is required by Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005. The FRA must be ‘suitable and sufficient’, and the local fire and rescue service has the authority to audit them. Where the building or the assessment is deemed unacceptable, the fire and rescue service may take enforcement action against the ‘responsible person’. The purpose of the FRA is to evaluate the risk to people from fire and enables the ‘responsible person’ (usually the owner, landlord or their agents) to determine the necessary fire safety measures required.

Under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order, the FRA only needs to consider the common parts of the block, but where a landlord has concerns about the risk to residents within their flats, the FRA may extend to the flats themselves. However in all cases the assessment should consider the fire resistance of the individual flat entrance door.

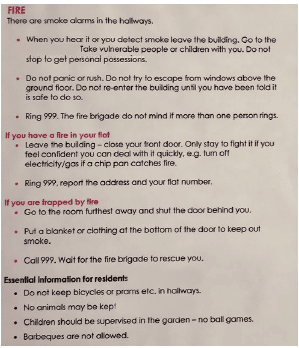

Figure 1 – This is part of a notice for residents of a three storey block of flats. It describes what to do in the case of a fire and is clearly not a ‘stay put’ strategy but helps to show this is a well managed block.

Intrusive fire risk assessments (involving destructive exposure) will only be necessary where there is justifiable concern regarding structural fire precautions. For example, it is common for FRAs to lift a sample of accessible false ceiling tiles, or to open a sample of service risers and so on. Some FRAs may have no intrusive investigations at all. They are nominally graded as follows and are self-explanatory:

- Type 1 – Common parts only (non-destructive)

- Type 2 – Common parts only (destructive)

- Type 3 – Common parts and flats (non-destructive)

- Type 4 – Common parts and flats (destructive)

A fire risk assessment need not always be carried out by specialists. For example, the landlord of a small, simple block of flats can act as the fire risk assessor and produce their own fire risk assessment using the appropriate guidance. Where the landlord is not confident to do this or where the building is particularly complex, then the ‘responsible person’ may want to employ a consultant to produce the FRA.

Here start the usual problems – how does the ‘responsible person’ identify a competent fire risk assessor? There seems to be a range of so called ‘specialists’ offering their services and judging by the commentary on a wide range of authoritative websites, the quality of the FRAs they produce is, at best, variable. For example, one of our associates is a Fire Risk Assessor. He submitted a fee quotation for producing a FRA for a variety of buildings on behalf of a potential client. Eventually he was thanked for the quote but told another consultant had undercut him on both cost and time. Then Grenfell Tower happened. A few days later he was contacted by the same organisation who had reflected on the process and asked him to carry out the work on his original terms and conditions.

If you have management responsibilities, here are a few tips that might help you assess the suitability of a Fire Risk Assessor:

- Whilst there is no requirement for an assessor to hold specific qualifications, a reasonable expectation is that they should be part of a third party accredited scheme where members have to meet the competency requirements of the Fire Risk Assessment Competency Council (FRACC). The FRACC has published a set of competency criteria.

- The better risk assessors generally have a limited scope of services. Beware of those offering a ‘onestop- shop’ for multiple regulatory needs – they are often ‘jacks of all trades’ without the detailed knowledge and training to deal with complex or high risk buildings;

- Does the assessment refer to the ‘type’ of assessment carried out, as described above? If not, it may not have been produced in accordance with the LGA Guidance which is the current accepted guidance document for purpose built flats;

- Refer to the ‘obvious signs’ section below. If the assessor has missed any of these then the validity of the assessor should be in doubt.

Although we have no detailed information on any of the following professional organisations, they all seem to run schemes that offer some form of review and/or audit process for their members:

- The Institute of Fire Safety Managers (IFSM)

- The Fire Industry Association

- The Institution of Fire Engineers

- Institute of Fire Prevention Officers

- The Fire Risk Assessment Certification Scheme

Whoever performs the function, the FRA should be reviewed regularly. Although no fixed periods are stated in the regulations, it has become good practice to review the document every year and/ or when something changes (for example, after refurbishments or repair, staff and legislation changes and so on). The LGA guide recommends a new assessment every two years.

A fire risk assessment must consider the ‘general fire precautions’ as defined in the regulations and usually includes the following:

- Measures to reduce the risk of fire and the risk of the spread of fire. •Means of escape from fire. Measures to ensure that escape routes can be safely and effectively used. •An emergency plan, including procedures for residents in the event of fire.

- Measures to mitigate the effects of fire. •Details of testing and maintenance of building services and of fire safety measures.

- Identification of the ‘responsible person’ (which may be a landlord, residents group etc) who is responsible for fire safety.

The FRA should conclude an Action Plan and this should set out a list of any (normally prioritised) physical and managerial measures that are necessary to ensure that fire risk is maintained at, or reduced to, an acceptable level.

4.0 Assessing the fire safety of purpose built flats

Most Residential Surveyors and Valuers are not qualified Fire Risk Assessors or Fire Engineers. Also, we are unlikely to have a deep, working knowledge of the building regulations or other relevant British standards and codes of practice unless we are also involved in design and specification work. Consequently, it is our view at SAVA/BlueBox that a residential practitioner’s approach to assessing the fire safety of purpose built blocks should be similar to that used for assessing building services in residential dwelling; namely: is there evidence all the appropriate approvals and supporting paper work are in place and, based on the appropriate level of inspection, are there any obvious visual indicators that suggests non-compliance. These are discussed in more detail below.

4.1 Evidence the block has all the necessary documentation

This evidence will vary depending on the nature, type and age of the block. However, the first step for a residential practitioner is to tell the client/ lender to ask their legal adviser to check whether all the appropriate ‘…valid planning permissions and statutory approvals for the buildings and for their use, including any extensions or alterations, have been obtained and complied with’.

For avoidance of doubt, alterations will include new cladding or replacing external finishes. Although this is the usual approach for most cases, given the complex nature of flat-related legislation and the events at Lakanal House and, of course, Grenfell Tower, it is our view this advice should be expanded and be more specific. You may find the following information useful:

“Because of the particular nature of the flat and the block within which it is contained, you should ask your legal adviser whether planning permissions and other statutory approvals for the buildings and for their use, including any extensions or alterations have been obtained and complied with. In respect of this flat, this should specifically include the following :

- A fire risk assessment (FRA) carried out within the last 2 years by a competent person who is a member of an insurance backed, third party accredited scheme.

- The FRA should cover all common areas and parts of the subject flat where appropriate. It should also cover the recent alterations within the flats in the block (carried out in approximately 2011), the over cladding (carried out in 2013) and the repair to the rubbish chutes (carried out in 2016).”

If appropriate documentation is not available, then an appropriately qualified and experienced person should investigate the matter further.

We have used some imaginary recent repairs to illustrate a number of issues but these are not uncommon for many older blocks. The length of this clause may not suit many lenders but we think residential practitioners need to be specific about what legal checks are required especially as many home buyers never meet their legal advisers who have no idea what the flat looks like or what it contains.

In addition to the FRA, you might also want to include some other approvals:

- If the block has been recently constructed, does it have the benefit of a warranty or guarantee? This is particularly important because many use ‘innovative forms of construction’ and unusual building materials and techniques.

- Building control approval, including evidence of some form of final certificate or final sign off. This will be relevant for both relatively recently built or repaired/renovated blocks. Although this did not prevent the Grenfell Tower fire, it does, at least, provide some form of benchmark.

- Evidence that the flat and the common areas are covered by appropriate electrical and Gas Safe certificates. Certificates should also cover unusual elements such as lifts and automatic gates although the managing organisation may have to provide these.

- Where water is stored, there should be evidence a legionella risk assessment has been recently carried by an appropriately qualified person.

4.2 Obvious signs of non-compliance

In a similar approach to that suggested for services (see ‘Assessing building services’ by Phil Parnham. RICS 2012), residential practitioners should not seek to confirm the actual flat and blocks conform to the documentation provided. Instead, you should look for obvious visual indicators that suggest the dwelling/building may not comply. Although you should not go beyond the scope of the inspection described in your terms and conditions, given the current public profile of the issue, you may want to follow those ‘trails’ a little more thoroughly.

The following information may be of use.

Figure 2 – This block was built in the 1970s. The hatch on the balcony floor was a formal part of the fire escape route if the fire blocked the front entrance door. The occupant was meant to lift the hatch cover and drop down to the level below (approx. height of 2.6metres). Something that is now beyond the 93 year old leaseholder.

4.2.1 Look out for signs of breaches of compartmentation especially inside the flat.

For example:

- The walls, ceilings and floors between the flat, common areas and adjacent areas, should all be in satisfactory condition without any holes or missing components.

- Spend additional time looking in storage cupboards or spaces where electrical cables, and pipes and so on pass through walls, floors and ceilings. These should be effectively sealed. Expandable foam is not a suitable method of fire stopping, and the pink fire resistant foams are unsuitable for larger apertures – beware of any above 20mm •Think about bathrooms, toilet rooms and kitchens. Where do the appliances drain to? Is there a common SVP? Does it seem to have appropriate fire separation? Where does the mechanical ventilation run? Mechanical ventilation systems played a key part in the deaths at Lakanal House in 2009, and any system other than one ducted direct to external air should prompt further questioning.

- Are there adequate escape provisions within the flat itself? Is the flat fitted with hard-wired fire alarms? Is there evidence these have been recently inspected and tested? Does the internal hallway (where present) have robust and resistant partitions, floors and ceilings?

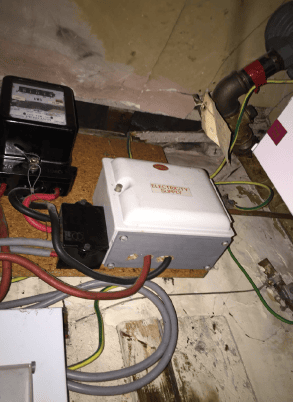

Figure 3 – This shows the meter cupboard ceiling within a flat. The joists to the floor above can clearly be seen where part of the ceiling has been removed so cables and gas pipes can be fitted through. This could a breach of compartmentation.

4.2.2 Do the common areas seem well-managed?

Typical indicators include:

- Are the stairwells/staircases clear of storage or rubbish?

- Is there emergency lighting (windowless stairs or above two storeys) and is it in a satisfactory condition or has it been broken and/or vandalised?

- Is there sufficient signage.

Typical examples would include:

- Advice about emergency procedures;

- Clear fire escape signs.

Figure 4 – This is a flat entrance door off the common staircase of a three-storey block. Although it appears in a satisfactory condition, the recessed panels could suggest it may not have a one hour rating.

- As you go up and down the stairs, look at the flat doors of the other dwellings. Do they look like fire resisting doors? Have some been replaced by the occupants? Are there any PVC doors ? (fire resistant UPVC doors are available but are rare and expensive).

- Are the finishes on the stairs and landings appropriate and in satisfactory condition?

- If there is a rubbish chute – is it in a satisfactory condition and is it maintained? If there are large bins at the base are these kept secure so they cannot be easily tampered with? Chutes should be separated from the stair by fire resisting construction, and ideally by a ventilated lobby.

- Are there any unprotected gas mains in the common areas or located in or adjacent to escape routes? •Look around the base of the block. Does it seem well managed? Is there enough space for fire service access? Is there evidence of illegal/chaotic parking blocking access for emergency services?

- Is there a means of ventilating the staircase? This usually takes the form of mechanically operated windows or rooflights, or dedicated smoke extraction systems. Is there detection in the stair to trigger the ventilation, or a fire service control at ground floor?

- Remember that with ‘stay-put’ policies, communal fire alarm systems are undesirable except in unusual circumstances as they are not usually properly maintained and tested.

- Has any external cladding system been fire tested? Has any recladding work received Building Regulations Approval? As we saw at Grenfell tower this does not necessarily guarantee it is suitable, but does at least defend your own professional position.

These are not a comprehensive list but represent what we think you should be looking for on valuation inspections, HomeBuyer Reports and Home Condition Surveys.

5.0 Conclusions

As the various inquiries and investigations begin to report their findings, we hope the true nature of the tragedy at Grenfell Towers will be revealed. Hopefully this will lead to a full, thorough and balanced review and revision of the current law and regulations and in turn will be reflected in changes to how residential practitioners value and report on the condition of flats in purpose built flats.

Until that time, we hope this article provides you with some useful information that will enable you to make balanced and reasonable professional judgements.