Asbestos Pipe Insulation.

In this article, Asbestos Surveyor, Callum Skene, explains the main three types of asbestos-containing pipe insulation and reminds us of the requirements for safe removal. He then explores some of the legal implications of asbestos in the context of residential property.

As we know, asbestos was used as a material in building products in the past because it had many great properties for the building industry: it was cheap, strong, insulating, and resistant to chemicals, electricity and fire. However, we now know that it is not so great for human health. Inhaling asbestos fibres can cause cancers such as mesothelioma and lung cancer, and other serious lung diseases such as asbestosis and pleural thickening – a lung disease where there is scarring, calcification, and/or thickening of the lining surrounding the lungs. According to HSE[1], in 2019 there were 2,369 mesothelioma deaths in Great Britain, and it is estimated that there were, in addition, a similar number of deaths due to asbestos-related lung cancer. There were also 490 asbestosis deaths due to past exposures to asbestos. So, it is a risk that should be taken seriously and considered at all stages of buying, selling or refurbishing a home.

What is asbestos?

There are different types of asbestos fibres; the three most common types are ‘blue asbestos’ (crocidolite), ‘brown asbestos’ (amosite), and ‘white asbestos’ (chrysotile).

Blue asbestos is regarded the most dangerous. The fibres are akin to tiny needles (short and sharp) as small as fractions of a micron, so can cause significant damage to the lining of the lungs. The structure of the fibres makes them easier to breathe in than other types of asbestos fibres, but they are also difficult for the body’s immune system to defend against due to their chemically-resistant nature. Blue asbestos was widely used as a spray-applied thermal insulating material and had many other heat resistant uses.

Brown asbestos is also highly dangerous, and is notably more common than blue asbestos. It can be found in insulating boards, as well as some less-considered items such as toilet cisterns and older bituminous products.

White asbestos has more flexible fibres and is considered slightly less harmful than brown and blue asbestos because it is more easily rejected by the immune system and exhaled. Before being banned, it was the most frequently used asbestos type in Britain. Due to the malleable nature of the fibre, it was woven into textiles and ropes, whilst also being a significant constituent in cement products such as corrugated sheets, flue pipes, and roof slates. Despite its weaker chemical resistance, it remains a dangerous material and was still responsible for many asbestos-related deaths. Any materials containing asbestos fibres, regardless of fibre type, are considered to be asbestos-containing materials (ACMs) in the UK and must be removed and disposed of as such.

Asbestos had numerous uses because it offers very effective heat, acoustic and chemical resistant properties. Although used in other sectors, notably marine engineering, it was very commonly used in the construction industry, for instance: in retardant coatings; insulation bricks; pipes and fireplace cement; heat, fire, and acid resistant gaskets; pipe and boiler insulation; ceiling insulation; firebreaks; decorative flooring; roofing and rainware; and even garden planters.

It is perhaps not fully recognised that the tragedy of the terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001 released a cloud containing approximately 400 tons of pulverized asbestos and other hazardous materials across lower Manhattan[2]. Tragically, there will inevitably continue to be deaths associated with the collapse of the twin towers for years after the actual event.

Although the dangers of asbestos had been known for some time beforehand (regulations were in place as an attempt to protect asbestos workers as far back as 1931[3].

), effectively all asbestos usage was finally prohibited in the UK in 1999, providing the ‘rule of thumb’ of presuming any construction prior to the year 2000 to contain ACMs.

This article focuses primarily on pipe insulation which contains asbestos.

Types of asbestos-related pipe insulation

The peak of usage of asbestos-containing materials for pipe insulation was from the 1940s to the 1960s. Asbestos thermal pipe insulation (or ‘lagging’) products were officially prohibited in the UK in 1985[4], though generally their usage had declined in the decade or so prior to that, owing to voluntary bans leading up to the cut-off. This is useful to know because, if you come across pipe insulation you know to have been installed after 1985 it is likely that it will not contain asbestos. However, there still remains a risk of ACM remnants being present beneath newer insulation on older pipework.

There are, in essence, three forms of asbestos-containing pipe insulation, or ‘lagging’, these are:

Air Cell or Celasbestos insulation

Usually installed in factory-moulded sections, this insulation is essentially composed of layers of corrugated asbestos cardboard clasped around a pipe and covered in foil. Although usually just containing white (chrysotile) asbestos, it is deemed to be ‘thermal insulation’ and is therefore a licensable material.

Figure 1: The above was taken from a very old brochure on asbestos materials by Bowen and Martin explaining the benefits of Celasbestos insulation.

Magnesia moulded block insulation

Again, pre-formed in factories, these sections of insulation are the closest relative to modern-day MMMF (man-made mineral fibre) sectional pipe insulation. Formed sections of magnesia and asbestos mixed blocks were clasped around pipework and often covered in a fabric wrap. Very rarely, boilers can also be found with brick-shaped asbestos magnesia insulation surrounding them.

Figure 2: Also taken from the Bowen and Martin brochure, explaining the benefits of asbestos magnesia moulded covering.

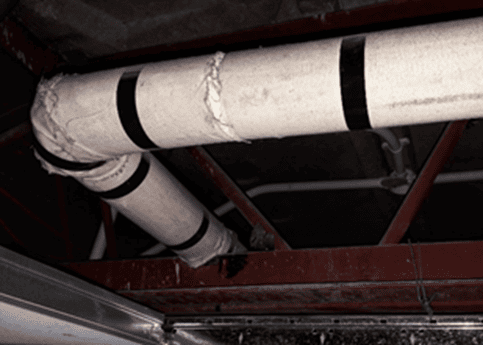

Hand-applied hard-set lagging

This was usually mixed on-site and applied onto pipework and boilers. Whilst some lagging was applied in a highly skilled and tidy fashion, at other times it was done haphazardly. As a result, quite often where this insulation has been applied, overspray can be found on the walls, floor and ceiling behind the pipe run that has been insulated, or around pipe brackets and fixings. In the present day, it is quite commonly seen wrapped in a calico plaster cast if managed well, but the original finish was usually just a thin layer of paint. The photographs below show an old “Robin Hood” oil-fired boiler with this type of lagging, now fully wrapped and encapsulated. The plaster cast acts as a tough material protecting the friable ACM beneath – if sealed completely it will contain the fibres and provide protection against small bumps and scratches.

Figure 3: Example of hand-applied hard-set lagging wrapped in a calico plaster cast. The walls behind have been encapsulated due to the presence of minor lagging residues or ‘snots’.

Figure 4: This Robin Hood cast iron sectional boiler dates back to the 1960s. It serviced a large warehouse before eventually being put out of commission. Beneath the galvanised steel casings are residues of more hard-set insulation, remnants of historic removal attempts.

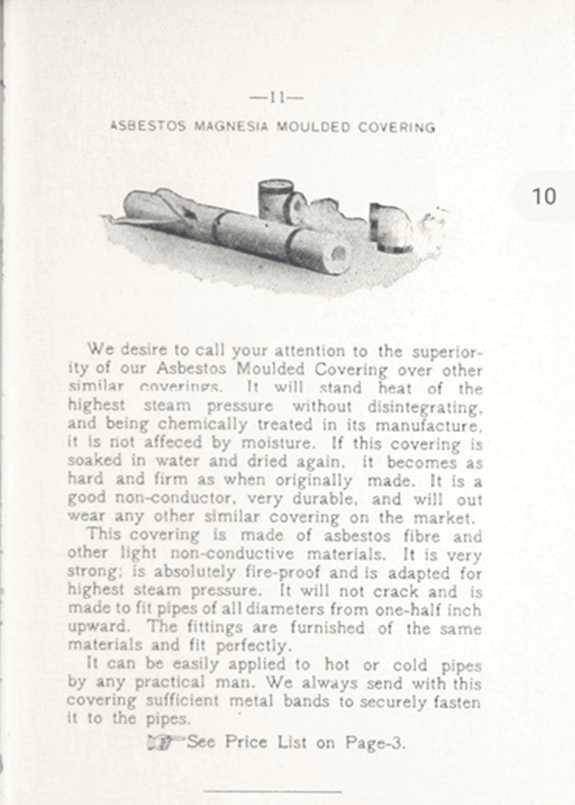

Figure 5: An example of asbestos magnesia sectional block insulation wrapped in a non-asbestos textile.

Figure 6: A long run of redundant pipe covered in highly damaged ‘air cell’ thermal insulation, found in the undercroft behind the boiler room in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 7: A close-up showing a cross section of this form of insulation. It is visually similar to cardboard, but the ‘corrugations’ are formed of paper containing high volumes of white asbestos.

The risks associated with pipe insulation

Asbestos pipe insulation is very friable in any form and often has a very high asbestos content. Unless fully encapsulated, this ACM poses a significant risk to building occupiers and therefore, remediation should be advised. Under CAR 2012, non-domestic properties must have an asbestos management plan compiled by the dutyholder of the premises – based on the management plan and the condition of the ACM, the insulation may be encapsulated if mostly structurally sound, or removed if encapsulation is not possible. Whilst domestic properties are not legislated under CAR 2012, best practice is to apply the regulations as though it were a commercial premise.

A comprehensive asbestos ‘refurbishment and demolition’ (R&D) survey will also identify if there are residues of this type of lagging to pipework where the insulation has been removed in the past. It is worth noting that asbestos removals 20+ years ago were nowhere near as comprehensive as they are today due to stricter regulations.

The regulations

Regulation 2 of the Control of Asbestos Regulations 2012 states that asbestos-containing pipe insulation (no matter what form or volume/ fibre type of asbestos it contains) is a ‘licensable’ material, and must always be removed under full enclosure by a licensed asbestos removal contractor, following a 14-day notification period to the Health and Safety Executive (with very few exceptions).

It is an offence to carry out work on an ACM that must be carried out by a licensed contractor. The HSE has comprehensive information on this here: https://www.hse.gov.uk/asbestos/licensing/licensed-contractor.htm

Because of the high risks involved and the use of a licensed contractor, removals of these ACMs can be extremely costly for residential properties.

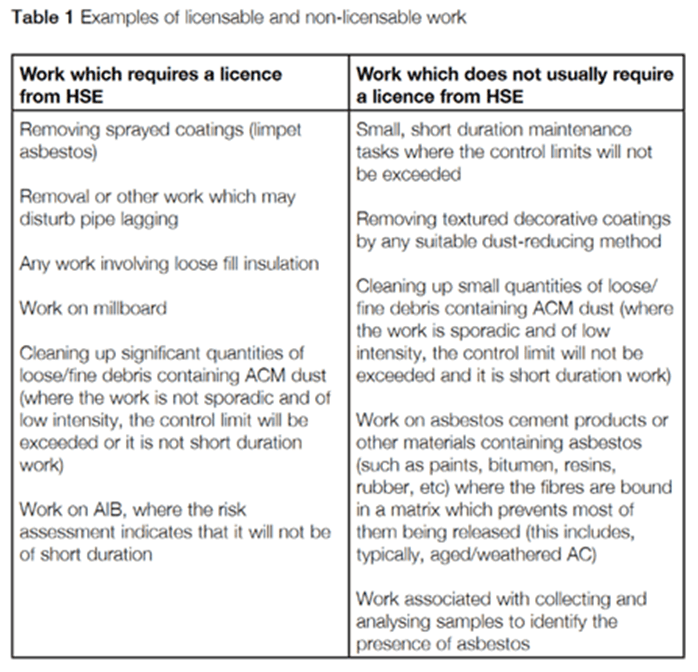

It is worth noting that not all asbestos removal has to be carried out by a licensed contractor. While most higher risk work with asbestos must only be done by a licensed contractor, there are some instances where a non-licensed, but competent contractor can carry out work on ACMs so long as the correct procedures are followed and appropriate equipment used.

These are listed in full on the HSE website at https://www.hse.gov.uk/asbestos/licensing/non-licensed-work.htm and includes things such as:

- Cleaning up small quantities of loose/fine debris containing ACM dust (where the work is sporadic and of low intensity, the control limit will not be exceeded, and it is short-duration work)

- Drilling of textured decorative coatings for installation of fixtures/fittings

- Maintenance of asbestos cement products (e.g. on roof sheeting, tiles and rainwater goods) and asbestos in ropes, yarns and woven cloth

- Painting/repainting AIB (asbestos insulating board) that is in good condition.

Any decision on whether particular work is licensable is based on the risk associated with the material.

Figure 8: Examples of licensable and non-licensable work from the HSE “Managing and working with asbestos – Control of Asbestos Regulations 2012”.

Legal duty of care

The Control of Asbestos at Work Regulations 2002 (updated most recently by CAR 2012) are very clear regarding non-domestic premises. There is a legal duty to manage asbestos in non-domestic premises, whatever business activity is carried out in them. In this instance, non-domestic premises include the common areas of residential properties, including halls, stairwells, lift shafts, and roof spaces in blocks of flats.

Therefore, since May 2004, every duty holder has to:

• find out whether your building contains asbestos, and what condition the asbestos is in

• assess the risk, for example, if the asbestos is likely to release fibres

• make a plan to manage that risk

The duty holder will be the person in control of maintenance activities. This could be the occupier, the landlord, the sublessor, or the managing agent. Sometimes no maintenance obligation exists, for example where there is no tenancy agreement or contract or where the premises are unoccupied and then the duty falls on the person ‘in control’ of the premises.

The duty holder should either label the asbestos, seal it, or remove it. The appropriate course of action will depend on the particular circumstances of the situation. If the asbestos is in good condition, the HSE recommends that a record of the existence of the asbestos is made on building plans or other records, that this information is kept up to date, and a register is set up of the location of the asbestos. Any contractors or building occupants likely to come into contact with the ACM should be made aware of its location.

Note, if a landlord is registered as a provider of social housing, then from 1 April 2013, fails or delays to act on an occupier’s report of asbestos in the premises, the occupier can also complain to the Housing Ombudsman Service following the appropriate complaint procedure.

Obligations to repair

Most people, once they know asbestos may be present in a building, are not happy, but the presence of asbestos itself does not constitute disrepair. It is only if it is damaged or deteriorates, leading to the risk of asbestos dust, that a duty holder should act to prevent disrepair from arising.

There are no specific laws or regulations regarding asbestos and housing. Landlords’ obligations arise under the legislation relating to:

• hazards under Part 1 of the Housing Act 2004

• statutory nuisance under the Environmental Protection Act 1990

• implied contractual rights under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985 and

• defective premises under the Defective Premises Act 1972

A landlord may also be compelled to act regardless of any legal obligation.

Asbestos and the Home Survey Standard

The new Home Survey Standard references health and safety on several occasions throughout the document and clearly, asbestos comes under this heading. But this is a complex area, particularly in the context of evaluating the risk and what it means for the client. So, we will return to this in another article.