Assessing the Safety of High-Rise Buildings.

by Phil Parnham MRICS

A year on from Grenfell Tower The fire at London’s Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017 was a human tragedy. As the disaster continues to be covered by the media and numerous investigations roll on, this article will focus on issues likely to be of concern to residential practitioners. As ever, we try to provide suggestions on both evaluating the issues and reporting to clients. We have to stress these are no more than our own opinions and you must evaluate any suggestions given yourselves as practicing professionals.

What type of cladding is causing the problem?

Understanding the cladding system is key to properly analysing situations such as Grenfell. Often called ‘rainscreen cladding’, this system has been around for more than 50 years, and over the last two decades has become the dominant cladding for most high-rise buildings. Typically, most systems are non-load bearing. External cladding panels consist of several components:

1. An outer skin of rainscreen cladding panels fixed to a metal supporting frame. The frame is fixed back to the structure of the building. Its main function is to protect from rain and improve the cosmetic appearance of the building. The panels do not provide thermal insulation.

2. A ventilated cavity. As it is impossible to exclude all moisture (particularly wind-driven rain on upper floors), the system includes a ventilated and drained cavity to tackle small amounts of water that get past the rainscreen. Most cavities are at least 25mm wide.

3. Thermal insulation. Usually fixed directly to the structure of the building. Depending on the manufacturer’s system, the outside surface of the insulation may be further protected using breathable sheathing felt. A wide range of materials are used including mineral insulation (such as Rockwool) or rigid foamed polymeric boards (such as Celotex).

4. An airtight vapour control layer. Usually positioned on the warm side of the insulation (often on the surface of the existing wall), this has two primary functions. The first is to reduce the amount of water vapour getting into the wall construction from the inside of the building and the second to provide a layer to reduce air leakage into and out of the building. If this layer is not airtight, wind-driven rain will be able to penetrate the building itself due to differences in pressure.

This rainscreen cladding must be sealed to other parts of the building façade, such as other types of adjacent cladding, windows and doors. If these seals are ineffective, it may not meet water and fire resistance standards. Fire-stopping is particularly important because if flames reach into the ventilated cavity they could quickly spread around the outside of the building. Typical locations of fire stopping include the junctions of the cladding and compartment walls and floors as well as around the windows and other openings.

Figure 1: A rainscreen over-cladding system fixed to an existing 1950s block, approaching completion. The rainscreen is solid aluminium panels with mineral wool insulation. If installed properly, this would probably be considered low risk.

Materials used

Various materials can be used as the rainscreen cladding layer, including fibre cement panels, solid metal sheets and composite sheets. The most common composite sheet consists of aluminium sandwiching a thin core of different filler materials, including calcium silicate or polyethylene. It is important to note that the composite sheets are relatively thin, usually between 3 and 7 mm thick and must not be mistaken for insulated cladding panels which contain thermal insulation.

Important Note:

The type of cladding used at Grenfell is an aluminium composite material (ACM). It’s important not to confuse this with another use of ACM, which usually denotes ‘asbestos containing materials’. It’s possible that clients may suffer from similar confusion.

Not the first

Although the tragedy at Grenfell resulted in the highest number of fatalities, it was not the first serious fire in a multi-storey residential block. Others include:

• Garnock Court,Irvine, Scotland, 1999. One person died and five were injured. Witnesses reported that a vertical ribbon of cladding on one corner of the block was quickly ablaze. The fire reached the 12th floor within ten minutes. Following the fire, plastic cladding and windows were removed as a precautionary measure and the Scottish Building Regulations amended.

• Lakanal House, Southwark, London, 2009. Six people died and at least 20 injured. An inquest found that botched renovations had removed fire-stopping material, which allowed a blaze to spread. The problem was not picked up in safety inspections carried out by Southwark Council. The council was prosecuted in 2017 and pleaded guilty to four charges concerning breaches to safety regulations and expressed “sincere regret for the failures that were present in the building”. Despite calls for a public inquiry, no further investigations were carried out.

• Lomond House, Charles Street, Glasgow, 2015. Fire spread up through eight storeys of this block owned by Glasgow Housing Association. The blaze came just two years after improvement works which enclosed balconies to make the flats warmer. After the fire, the housing association improved fire-stopping in the block.

These three examples together with numerous others from around the world clearly show that fire safety of high-rise blocks has been a concern for decades.

What caused the fire at Grenfell?

Much has been written about the cause of the fire at Grenfell, and almost a year later new revelations appear on a regular basis. Because of the ongoing inquiry and the various criminal investigations, we won’t attempt to review such a complex case – we simply could not do this justice. However, to carry out effective assessments of residential flats in high-rise blocks, particularly at home buyer and building survey level, it’s useful to understand some of the emerging facts:

• The main reason for the rapid spread of the fire is likely to be the type of rainscreen cladding panels. They were Reynobond PE panels, consisting of two coated aluminium sheets, laminated to both sides of a flammable polyethylene core.

• A rigid polyisocyanurate (PIR) foam was used to thermally insulate the existing walls of the building behind the rainscreen. This rigid insulation burns when exposed to heat and gives off toxic cyanide fumes.

• Evidence continues to emerge about the effectiveness of the fire- stopping within the ventilated cavity. Many commentators suggest the ‘chimney’ effect of an open cavity allowed the quick spread of the fire.

More facts will emerge as inquiries progress, but these factors have driven much of the government’s response to the disaster.

Government action

In response to Grenfell, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) established the ‘Building Safety Programme’ (BSP) to cover high-rise residential buildings, including hotels. Its aim is “to make sure that residents of high-rise buildings are safe – and feel safe – now, and in the future”. With support from local fire and rescue services and a panel of independent expert advisers, the BSP supports building owners in taking immediate steps to ensure their residents’ safety and in making decisions on any necessary remedial work.

The panel advised the government to identify the type of ACM used in any residential building over 18 metres tall. This was to ensure the cladding was of ‘limited combustibility’ and that it meets current Building Regulations guidance on external fire spread. To help in this process, cladding samples were tested by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) free of charge, but the building owners were responsible for collecting the samples. In July 2017, the panel also recommended large scale testing of whole cladding systems to understand the way in which different types of ACM panels behave with different types of thermal insulation in a fire. These tests were carried out by the BRE in accordance with British Standard 8414 and involved building a 9-metre high demonstration wall with a complete cladding system. The findings were communicated to owners of residential blocks through various channels.

Identifying the type of ACM

ACM cladding can’t be identified visually, as solid aluminium sheets look the same as aluminium composites, particularly from ground level. An ACM can only be properly identified by inspecting a cut edge of a panel. Even then, the nature of any filler material can only be determined through laboratory tests. Owners of potentially affected blocks must provide two samples from the same building, both above and below 18 metres from the ground. This particular test identified three types of ACM, categorised by the filler used:

• Category 3 ACM (least fire resistant). Two sheets of aluminium with an unmodified polyethylene filler. The type used on Grenfell.

• Category 2 ACM. Two sheets of aluminium with a fire-retardant filler.

• Category 1 ACM (most fire resistant). Two sheets of aluminium with a limited combustibility filler.

It is also necessary to understand the interaction between cladding panels and the thermal insulation, along with any cavities and voids that need to be fire-stopped. The large-scale tests investigated this relationship.

Advice from the BSP

Rather than go through the detailed and complex results, we have reproduced part of the summary from the Building Safety Programme (update and consolidated advice for building owners following large scale testing) issued in February 2018:

• Category 3 ACM presents a significant fire hazard on buildings over 18m with any form of insulation.

In our view, this means this type of cladding does not meet the building regulation standard under any circumstances.

• Category 2 ACM:

o presents a notable fire hazard on buildings over 18m when used with rigid polymeric foam- based insulation on the evidence currently available.

o can be safe on buildings over 18m if used with non-combustible insulation (e.g. stone wool), and where materials have been fitted and maintained appropriately, and the building’s construction meets the other provisions of Building Regulations guidance, including provision for fire breaks and cavity barriers.

In our view, this means that the nature of the thermal insulation and how the cavities and other junctions are fire stopped are critical to the safety of this type of cladding.

• Category 1 ACM can be safe on buildings over 18m with foam insulation or stone wool insulation, if materials have been fitted and maintained appropriately, and the building’s construction meets the other provisions of Building Regulations guidance, including provision for fire breaks and cavity barriers.

The scale of the problem

Based on figures released by the Building Safety Programme in March 2018, the total number of residential and public buildings in England fitted with Aluminium Composite Material (ACM) and over 18 metres tall was 319.

Of these, 306 have ACM cladding systems that are unlikely to meet current Building Regulations guidance and therefore present fire hazards, according to the panel of experts.

Of these 306 buildings:

• 158 are social housing buildings (managed by local authorities or housing associations)

• 134 are private sector residential buildings, including hotels and student accommodation

• 14 are public buildings, including hospitals and schools.

Of the 158 social housing buildings that failed large-scale system tests, 65% (103) have begun remediation. Just seven have completed. Data is still being collected on progress of private sector buildings. This information is held centrally and while getting access to a database of affected blocks would be very helpful in the valuation process, it’s not that simple. According to the Guardian (16 March 2018), concern over terrorism and arson has led to councils and landlords keeping the location of affected blocks secret. One council-owned block in Berkshire with combustible insulation has been attacked by arsonists several times and many affected blocks have 24-hour fire wardens. It is important to build up your knowledge of residential blocks in your local area. Local press and media are a useful source of information as the issue still attracts a great deal of public interest.

Scale of remedial work

The BSP points out the complexity of remediation work on affected buildings. It involves broader fire safety systems, typically including provision for escape, compartmentalisation and fire-fighting equipment. Although the nature of remediation schemes will vary between blocks, for most Category 3 ACMs, removal and replacement is the only safe option.

Figure 2: Local authority residential block with Category 3 ACM installed in 2009. It was removed, and replacement is still under discussion.

Private residential blocks

To gain an insight into how this has been affecting private residential blocks, we have included three typical examples:

Blenheim Centre, Hounslow

Mixed commercial and residential development, owned by Legal & General who announced ownership of the entire, multi-million-pound cost of removing the Grenfell-style cladding to the flats above the Blenheim Centre. Therefore, the 334 residential leaseholders at the flats will be spared repair bills estimated between £20,000 and £30,000 for each flat. As an interim measure, 16 fire marshals have been employed 24/7 at a cost of £165,000 a month.

Citiscape, Frith Road, Croydon.

Residential complex with 93 dwellings with ACM cladding. It’s estimated it will cost £2 million to make the block safe, as well as £20 000 a month for fire marshals. FirstPort, the Property Managers took the issue of liability to a tribunal. In March 2018, the London Residential Property First Tier Tribunal ruled against the leaseholders, insisting they should pay because ‘if the manager is obliged to do work … the tenants are obliged to contribute to the cost although they remain entitled to dispute the reasonableness of the cost’. Following this announcement, Barratt Developments announced it will pay for the remediation work and the backdated and future fire safety costs, saying: “Citiscape was built in line with all building regulations in place at the time of construction. We don’t own the building, or have any liability for the cladding. The important thing now is ensuring that owners and residents have peace of mind.”

Sesame Apartments, Battersea, London

According to the Guardian (19 April 2018) residents of 80 flats are each facing bills of up to £40,000 because the building is clad with ACM panels. Leaseholders were told by the managing agent that the freeholder would not be responsible for the costs. It seems the leaseholders are about to receive £8,000 bills to cover a new fire alarm and the cost of a 24-hour watch in the building, but it’s the potential £2.2m bill for replacing the combustible panels that is most concerning. The managing agent said it hoped insurers and warranty providers would pay the bill. These three different outcomes show how difficult it is to predict not only how the safety issues will be resolved, but who will pay.

Buildings under 18m tall

The BSP focuses on residential blocks higher than 18 metres, as this is the criterion contained in Approved Document B of the Building Regulations and usually equates to blocks of 5/6 storeys and higher. However, what if a residential block of less than 18m high is clad with a Category 3 ACM over a polymeric insulation layer? Does this pose any less of a risk? It could be argued that occupants would notice little difference between a four or sixth floor flat when fire is rapidly spreading across the block’s façade.

The Local Government Association says:

“Buildings less than 18 metres tall are not subject to the same requirements in terms of cladding. However, we will be working with the Government to take account of the learning from all this work in reviewing current regulations and requirements”.

This echoes advice included on the website of the Building Safety Programme:

“The government is working with the Expert Panel to consider whether there are any heightened risks linked to other cladding systems and broader fire and building safety issues in high rise buildings”.

In our view, this clearly suggests that when the highest risk installations are resolved, the government will consider other less urgent problems, which could include lower rise blocks clad with ACM panels. Watch this space.

Advice from RICS

Following Grenfell, the RICS issued several guidance notes:

• Valuation – Tower blocks and cladding: valuation statement.

• Technical –a briefing note produced by Gary Strong FRICS Director of Practice Standards & Technical Guidance (RICS). This is aimed at practitioners looking at remediation options for clients.

• A Video update by Gary Strong

Although RICS cannot be prescriptive about what valuers should do or say, their valuation statement gives useful reminders on handling uncertainty:

• Where there is considered to be a material uncertainty around a valuation these uncertainties should be clearly articulated. The revised RICS Valuation – Global Standards (Red Book) 2017, effective from 1 July 2017, addresses how to deal with this in sections VPS 3.2.2 (o) and VPGA10. This states that the addition of a commentary around uncertainty is only mandatory where the uncertainty is material. In addition, the use of an uncertainty clause should only be employed in exceptional circumstances and must be proportionate to the case i.e. the prevailing uncertainty really only relates to high-rise or high-risk buildings.

• Where a decision on how much explanation and detail is necessary concerning the supporting evidence, the valuation approach and the particular market context needs to be made, it makes it clear that this is a matter of judgment in each individual case. In any event, RICS standards advise that it would not normally be acceptable for a valuation report to have a standard caveat to deal with unspecified material valuation uncertainty. The degree to which an opinion is uncertain will normally be unique to the specific valuation, and the use of standard clauses can devalue or bring into question the authority and professionalism of the advice given.

Although many RICS members would have preferred clearer advice from their professional institution, dealing with uncertainty is always a challenge and must be dealt with on a case by case basis. Two points can be made:

• The problems associated with high-risk cladding on high-rise buildings clearly constitutes a ‘material uncertainty’ if the constructional type is not known.

• It is not acceptable to use a standard caveat simply because a property is in a high-rise residential block. There must be a clear ‘trail of suspicion’ that justifies the expression of uncertainty. For example, many modern blocks are clad with non-combustible material (such as brick or stone) and although we will not know for sure whether the cladding conforms to all the building regulations, there may be little justification to call for further investigations.

Advice from lenders

Although RICS must be measured and objective, lenders and surveying organisations are more prescriptive about what they want to see in a report. We have found some examples that could help to establish current norms across the sector.

• General advice to valuers from large surveying company – “The tragic events at Grenfell Tower put the spotlight on fire safety in large blocks of flats. Where a valuer has uncertainty over the type of cladding or other fire safety measures then, in consultation with our lender client and in the absence of any other specific reporting requirements, the guidance to the valuer is to recommend further investigation prior to confirming value”.

• Specific advice to valuers from a lender – “Valuers should express caution around fire safety. Discretion can be used on blocks which for example are traditionally brick clad. However, where the block has any aspect which could be considered to impact the safe occupation and marketability, including other forms of external cladding, Valuers should return a zero value until proof has been received that the block meets Building Regulations and the testing requirements outlined by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). For the block to be suitable for lending, proof must be obtained from the landlord that Building Regulation and testing requirements have been met. This proof can be obtained pre or post inspection, but a zero value must be returned until provided”.

• Clause to include in a valuation report from a large surveying company – “The building has external cladding. In the light of recent events, a report is required from a Fire Safety Officer or a Structural Engineer with appropriate fire prevention experience confirming that the property has been inspected post-14 June 2017 and the cladding system confirmed to meet current requirements.”

The problems with assessing properties in high-rise blocks

Even before Grenfell, lenders never liked tower blocks. Here is a list of factors that could affect their decision to lend:

• Is the block a Large Panel System or other prefabricated system?

• Are the service charges high and/or escalating?

• Is there evidence of poor security, vandalism and crime in and around the block?

• Does the block have lifts (especially important if it is above four storeys high)?

• Is there a limited history of re-sales on the open market?

• Is there evidence of proactive estate/block management? and

• Is the mix of tenants and owner-occupiers sensibly balanced?

Add in the issue of ACM cladding and it is not surprising that many high-rise flats do not measure up.

Many lenders will accept flats in high-rise blocks if they are good quality, modern, ex-local authority, medium and high-rise purpose built or converted flats in prestigious areas of city centres.

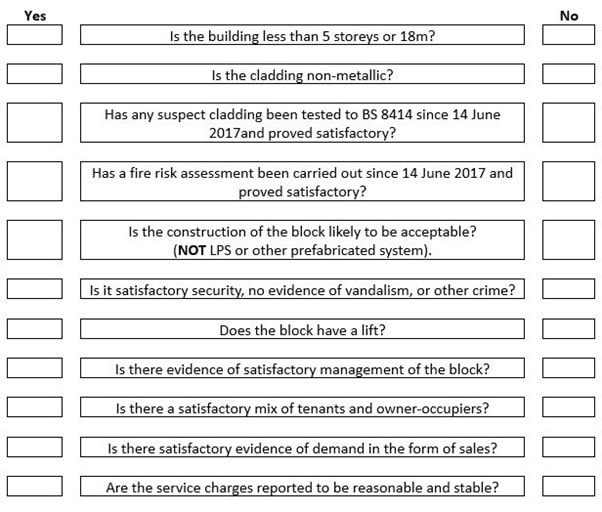

BlueBox Partners protocol for assessing high-rise flats

To help with decision-making, we have produced a protocol that may be useful for residential practitioners.

WARNING: It is designed to help you come to a view based on the evidence you collect. This is NOT a process that automatically provides you with the ‘right’ answer. Instead it puts you in the right ‘ball park’ so you can then make your own decision. This protocol should:

• Pose the most important questions.;

• Help show that you have followed a rational process.

• Provide a record for your files.

Tick the appropriate box. The more ‘yes’ responses, the more likely the property will be acceptable. The more ‘no’ responses, the less likely the property will be acceptable and the greater the justification for further recommendations. This is not a numerical exercise but can provide a more objective basis for assessment.

Typical report phrase

These questions cover a wide range of characteristics of high-rise flats. Rather than cover all the issues, we have included a phrase/paragraph that relates only to the cladding of a block. If you are concerned about the cladding, the following phrase may work for a HomeBuyer Report (or level 2 equivalent):

Part of this block is covered with metal faced cladding panels (describe which part). Government tests have shown some types of cladding panels can pose a serious fire risk. Not only will this put the occupants at a safety risk, it can also result in higher property insurance premiums, costly management charges and expensive large-scale remedial work. This will impact on value. The vendor/landlord/freeholder should provide sufficient proof that the cladding and the rest of the building meets the requirements laid down in the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government ‘Building Safety Programme’ (including the latest monthly updates).

If this is not provided, you should not proceed with the purchase.

The precise content depends on the nature of the property, but such a situation would warrant a condition rating three (further investigation), a nil valuation (if appropriate) and clear warnings to the client about proceeding with the purchase.

Further investigations – what type and who should carry them out

One of the problems with recommending an issue needs further investigation is the client will phone you straight back and ask who should carry it out. Cladding tests should be done by an assessor employed by a test laboratory accredited by the UK Accreditation Service to carry out tests in accordance with BS 8414 and classify results to BR135. However, the BRE are currently doing this for free. For fire risk assessments, the National Chief Fire Officer Council recommends you choose someone from a professional body that operates a certification scheme for fire risk assessors and fire risk assessment companies. They have a very useful guide on how to find and appoint an appropriately qualified person.

A review of the building regulations

Shortly after Grenfell, the government announced it was going to carry out a review of the building regulations and fire safety. Led by Dame Judith Hackitt, its purpose was to make recommendations that will ensure there is a sufficiently robust regulatory system for the future and to provide further assurance to residents. The review examined the building and fire safety regulatory system, with a focus on high-rise residential buildings. An interim report was published in December 2017 with the final report (Building a Safer Future’) appearing in May 2018.

Interim report and final reports – key findings

The interim found that the current regulatory system for ensuring fire safety in high-rise and complex buildings was not fit for purpose. ‘This applies throughout the life cycle of a building, both during construction and occupation, and is a problem connected to the culture of the construction industry and the effectiveness of the regulations.’

The final report was equally damming. Dame Judith found ‘…that Indifference had led a “race to the bottom” in building safety practices with cost prioritised over safety’. However, because the report stopped short of recommending a ban on flammable cladding, it was criticised by a number of groups including the survivors and the bereaved family members. So fierce was the reaction, the government announced they would consult on banning flammable cladding.

It is beyond the scope of this article (and of its author) to provide a full Account of the current situation because it is rapidly changing. There is a clear indication that a complete overhaul of building regulations and associated legislation will occur in the near future. It is important that all residential practitioners keep up to date with developments as the implications are considerable even for those not involved with high rise buildings.

Further sources:

Here are the most useful sources of information:

Building Safety Programme: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/building-safety-programme

RICS: http://www.rics.org/uk/news/grenfell-tower/

National Fire Chiefs Council: https://www.nationalfirechiefs.org.uk/Home

Local Authority Building Control: https://www.labc.co.uk/news/grenfell-updates-and-statements