Japanese Knotweed – Research by Dr Dan Jones.

Fall from grace

Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica var. japonica), is one of a number of knotweed species, introduced into Europe in the mid-19th century (1841) by Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold, a German botanist and physician living in The Netherlands. In 1850 he sent a specimen of Japanese knotweed to Kew Gardens in London. Kew offered the plant for sale to local commercial nurseries, and by 1854, knotweed had travelled as far as the Royal Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh.

Since first escaping from cultivation in Maesteg, Wales in 1886, Japanese knotweed now has a well-established range across the UK. It is found in over 70% of the UK hectads – 10km×10km grid-squares that are used to see how widely distributed plants and animals are. It is worth noting that although knotweed may be present in these hectads, it is not necessarily abundant throughout each grid. Further afield, knotweed is now established across mainland Europe, North America and the Southern Hemisphere. This global spread is astonishing; particularly, as to date, this has mainly occurred via plant fragments (vegetative) and not from (viable) seed.

Figure 1: Japanese knotweed in flower, Cardiff.

© Advanced Invasives 2018

From a horticultural perspective it is clear why knotweed was so prized for planting schemes: it is easy to propagate (spread), growing rapidly from early in the growing season to 2.5m tall and it is visually striking – particularly in the summer and autumn months when it produces abundant creamy-white blossoms. However, as an ecologist, plant ‘traits’ such as ease of propagation and spread are precisely why knotweed has, and will continue to be, quite literally a huge problem; both for native biodiversity and increasingly, wider society.

Figure 2: Who’s problem is it? A Japanese knotweed issue that can’t be ignored in Cardiff.

© Advanced Invasives 2018

Figure 3: Where do you start? Japanese knotweed growing along the headwaters of the River Rhymney in South Wales, crossing public and private property boundaries. Who is responsible for the control of such infestations?

© Advanced Invasives 2018

From the past to the present

With the benefit of hindsight, it can be all too easy to be critical of historic events. However, this story continues to develop into the present, as successive cycles of legislation and poorly-evidenced knotweed control practice have continued to drive further spread of knotweed in to the national consciousness and print media of the UK.

In the UK alone, it has been estimated that Japanese knotweed control costs the UK economy c.£170 million per annum. But, until now, there has never been a study of the scale needed to truly test how effective these treatments are. They are being sold to home and landowners with no unbiased research to back up their worth. However, we have recently completed the largest Japanese knotweed field trial ever conducted globally, and working with academic and industry partners, found the best way of treating the plant long term.

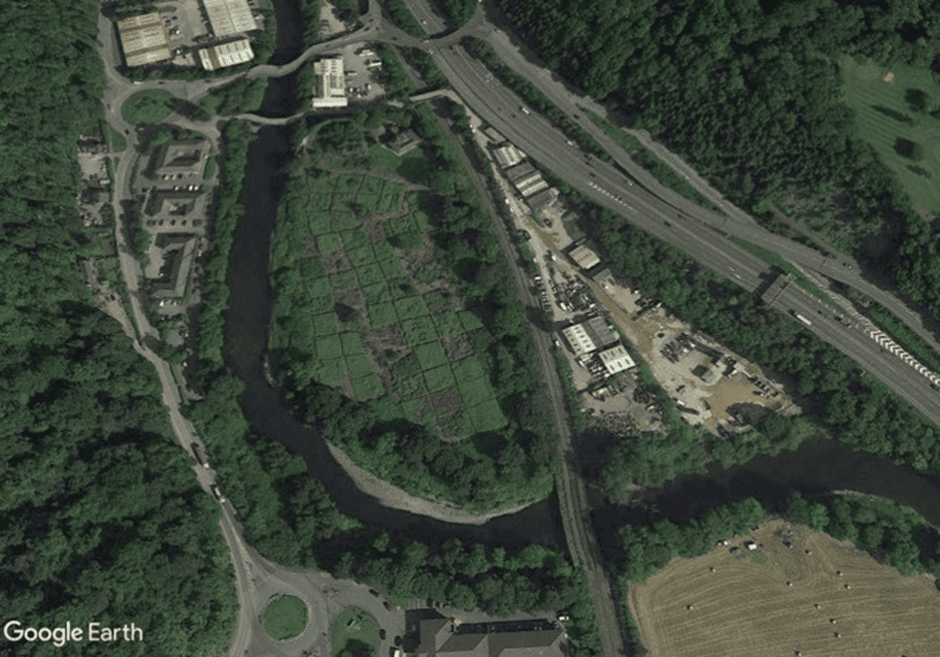

Figure 4: Aerial view of the Invasives Research Centre (IRC) in Taffs Well, near Cardiff.

© Google Earth 2018

Control not kill

The key to our approach was to understand the plant, in order to control it. Japanese knotweed’s ease of spread and rapid growth from a deep rhizome (root) system was initially prized for planting schemes. During our research, it became apparent that because a Japanese knotweed stand contains significant underground and spreading biomass, we would need to do large field trials, to reflect real world conditions. So, we set up 58 different 15 metre × 15 metre (225 square metre) field trial plots, located in south Wales (UK), and repeated each method three times in these areas.

Between 2011 and 2016 we benchmarked all 19 of the active control methods and herbicides used for controlling knotweed in the UK, Europe and America. This experiment continues to be unique in terms of scale, duration, and scientific rigour and is the largest Japanese knotweed field trial ever conducted, globally. It is plain to see why this research has not been conducted before – the commercial cost has been (conservatively) estimated at £1.2 million. However, given the on-going costs of managing knotweed in the UK, the value of the experiment is self-evident.

Through our research, we have defined a new patent pending approach to Japanese knotweed treatment; The 4-Stage ModelTM. This model links herbicide selection and application with the seasonal surface-rhizome flows in the knotweed plant. Within the first three years of the experiment reported on here, we found that glyphosate-based herbicides control aboveground knotweed growth significantly better than all other herbicide groups currently used for knotweed control. We also found that physical methods such as covering simply do not work. Importantly, we are not describing eradication (which is almost impossible to achieve in short timeframes using herbicides), but rather a type of extended “dormancy” where the plant does not grow above ground.

Figure 5: Plot comparison before and after treatment at the Invasives Research Centre (IRC) in Taffs Well, near Cardiff.

© Advanced Invasives 2018

Moving forwards

Now, we are using our research to replace out-dated guidance based on short-term experiments and anecdotal information; in short, we’re discovering how best to tackle invasive plants in real-world conditions, informed by the evidence of what actually works.

About Dr Dan Jones

Dan is Managing Director of Advanced Invasives Limited and an Honorary Researcher in Swansea University Department of Biosciences. Dan has a particular interest in applying scientific understanding of invasive plant ecology to real world problems.