Gas Busters (Part 2).

In Gas Busters (part 1) we wrote about of some of the activities and items to look out for when surveying any given property which has a gas installation of some type. In this issue, we will start to provide a little more detail on achieving a better understanding of gas appliance installations and how to identify warning signs for dangerous installations.

It is certainly worth again reiterating at this point that there are stringent regulations in place around working with gas, and any individual who is able to work on gas, must be deemed as competent. Competence in the eyes of the HSE is to be an approved member of the Gas Safe register, and hold the specific qualifications relating to whichever appliance is going to be worked on.

So when am I ‘working on gas?’ Well, possibly the most common misconception for many non registered individuals who have a vested interest in reporting on and determining the safety of a gas installation, would be relates to boilers, and specifically, boiler cases.

Where there is a boiler present in a property, and it is a ‘room sealed’ appliance, unless you are Gas Safe registered, you cannot remove the outer casing of the appliance to check for data information etc. The casing structure on many (not all) room sealed boilers, forms part of the actual integrity of the combustion process for the appliance, and as such there are sealing strips and gaskets in place to ensure the safe operation of the appliance. Where a case is removed from the appliance and subsequently replaced, the only true way of ensuring that the gas and air mixture and combustion process has not been compromised is by conducting a combustion analysis check on the appliance with a calibrated analyser.

So, as a rule of thumb, if you need a screwdriver or any tool whatsoever to check an appliance, you are probably overstepping the ‘competence’ mark.

Keep the term ‘visual inspection’ clearly in your mind and you will not go far wrong but be clear that not being able to open the boiler casing to correctly identify the boiler make will be a limitation of inspection.

We have put together a small checklist for overall thoughts and consideration, which should be a useful way of considering all gas safety requirements:

1. Gas safety legislation and Standards

There are a number of publications relating to safe operation for gas installation activity, and one useful document to have printed out and kept with you in the event of uncertainty is the Industry unsafe situations procedure. This document is the primary driver for knowing how best to respond/act on a dangerous installation.

2. Gas emergency actions and procedures

In accordance with the GIUSP publication, if you Identify an installation which you regard as suspicious or potentially dangerous you must respond reasonably: You should seek professional advice immediately and advise the ‘responsible person’ to turn off their gas supply at the main spending a visit from a competent and authorised person.

3. Products and characteristics of combustion

There are over 100 admissions to hospital each year from suspected carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning, and around 50 fatalities. Carbon monoxide is far more likely to be the cause of a dangerous situation than, say, a gas explosion.

CO is created where a flame is burning without a sufficient oxygen supply, and where this occurs, the products of combustion create a much higher concentration of CO. Where these products find themselves spilling into a living area, then the potential for CO poisoning is clearly heightened.

As the majority of boilers are now room sealed appliances, very few are likely to spill products of combustion into a living area. Even so, and where possible, it is always worth visually inspecting the seam along the case structure for any signs such as brown marks identifying leakage of fumes.

Far more likely to create a dangerous situation will be an open flued gas appliance, such as a gas fire in a living room. It is always worth checking the chimney pots/termination as you walk into a property to establish that there are appropriate pots installed for a gas appliance, as this can be a good early indicator of potential dangers. Once inside the property, look for any evidence of staining or scorching around the tops of gas fires which may indicate an issue.

Some appliances have a requirement for an air vent within the room, and unfortunately there is a natural tendency during the winter for the home owner to block up the vent and get the fire burning at full blast. If the home owner also has draft exclusion installed and double glazing etc. this technically starves the appliance of any oxygen, and will be slowly poisoning the occupants every time they turn on the appliance. It is, therefore, well worth checking for cling film/wall paper over any of the vents.

4. Ventilation

As mentioned above, good ventilation is critical to the burning of an open flued appliance, and it is imperative that any air vent installed for this purpose is clear of obstruction, does not have a fly mesh installed, and is not closeable.

5. Installation of pipework and fittings

It is always worth running your eye over as much of the visible gas pipework as possible, from the gas meter right through to each appliance, allowing for the fact that much of this will not be exposed.

It is also worth checking to ensure that all visible pipework is suitably secured and stable and that there is no sign of corrosion or other damage or anything that might compromise the tightness of the system.

6. Using your nose

Clearly any indication of gas escapes or smells that could be caused by fumes should be immediately reported to the person who is responsible for the premises. Such incidences are classed as ‘immediately dangerous’ because if the installation is used it will constitute a danger to life or property.

In practical terms the only person who can legally allow a gas supply to be disconnected is either the gas supplier or the ‘responsible person’ and only a gas engineer can make such an installation safe by, in effect, putting the appliance or installation beyond use by physically disconnecting it from the gas supply. If the responsible person refuses to allow this, then the gas engineer must notify the gas supplier who must then take action to make the installation safe.

In practical terms, a surveyor may not have contact with the responsible person. If the home owner is not present during the survey and if the surveyor has this suspicion, then the best option is to immediately abort the survey and report this concern to the agent and ask them to contact the ‘responsible person’.

Clearly there is a duty of care placed on the surveyor in such a situation so we have also checked with the legal team at the Insurers on this point.

They confirmed the following:

“A ‘better safe than sorry’ approach is the best for this kind of situation – the surveyor should try and ensure that they bring it to the attention of the relevant parties as promptly as possible. If the surveyor is able to speak to the responsible person directly at a later time and alert them to the matter, then it would be prudent to do so.

From a legal perspective, however, it is correct in saying that as long as the surveyor does notify the sales agent, then they should be in the clear. Ultimately, the sales agent represents the vendor, and under agency law, notifying the agent of the problem would have the same effect as telling the vendor.”

7. Chimneys and flues

Open Flued Appliances

If there is an open (sometimes called conventional) flued appliance in a room, such as a gas fire, and the appliance is ventilated via a chimney then, as a surveyor, you can still make a visual check. The products of combustion (POCs) travel up the flue in the chimney by natural draught or ‘flue pull’ and clearly anything that impedes the flue pull will compromise the discharge of the POCs.

There are four main parts of the flue – the primary flue and draught diverter (usually part of the appliance itself), the secondary flue and the terminal, which is fitted to the top of the secondary flue.

The purpose of the terminal is to:

• Help flue gases discharge from the flue

• Prevent rain, birds, leaves etc. from entering the flue and compromising the safety of the appliance

• Minimise down draughts

The terminal must be suitable for the appliance type fitted to the flue. Terracotta chimney rain inserts are not suitable for use with gas appliances. If a terminal is missing or not appropriate this should alert you to the need for further investigation even if a Gas Safety certificate is present. (remember, like an MOT or indeed a survey, the Gas Safety Certificate will only report on what the gas engineer finds on the date of the inspection and it is perfectly feasible for something to have changed between the gas engineers visit and the date of the survey).

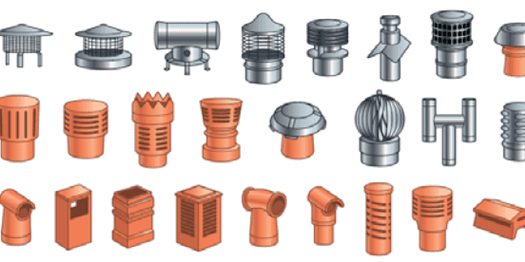

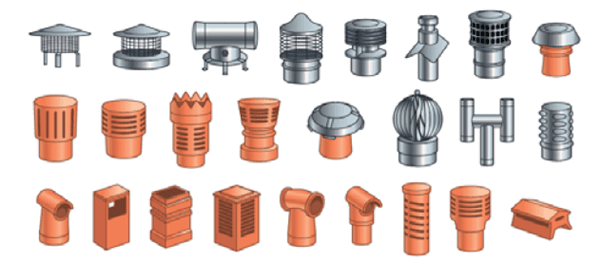

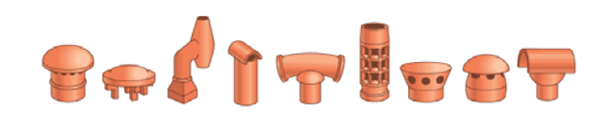

Below are examples of acceptable flues. However, it is important to realise that flue suitability is dependent on the type of appliance to which it is connected.

Chimney caps, such as those shown here, are not suitable to be used as a ‘terminal’.

Room Sealed systems

With these systems the air intake and POC outlet are at the same point. In practical terms there is greater flexibility as to where these appliances can be fitted but it must be within the vicinity of an external wall or roof termination.

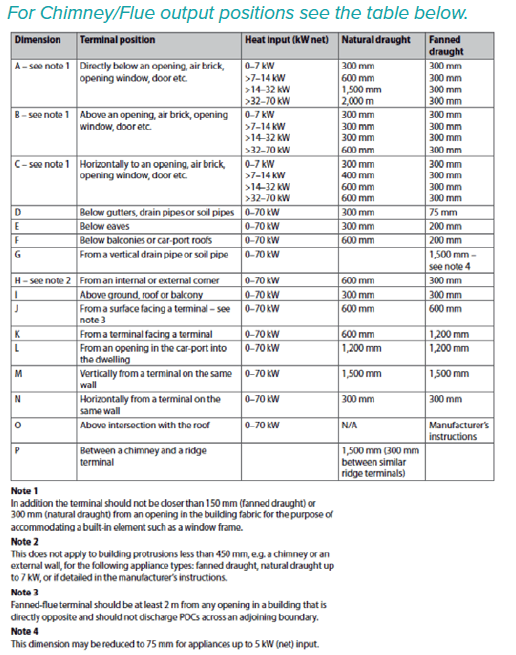

The POC outlet and air intake are at the same point and so at equal pressure, hence the term ‘balanced flue’ is often used. With a balanced flue the terminal will be part of the appliance but must be located so as to:

• Prevent combustion products from re-entering the building (not immediately below an opening such as an airbrick or window)

• Allow free air movement

• Prevent any nearby features/obstacles from causing an imbalance around the terminal.

In practical terms it is unlikely, though not impossible, that an appliance was incorrectly installed in the first place. What is more likely is that a building alteration has been undertaken which has compromised the safety of a balanced flue. (A classic example would be constructing a conservatory around a flue terminal and when surveying a property you should be particularly alert to such situations).