Structurally Insulated Panels.

What the SIP are they?

Do you remember the good old days when residential dwellings were defined as one of two types: traditional or non-traditional. The latter category conjuring up negative images of poorly built post-war technologies and materials. In the 1980s, the construction industry got caught up in the rush to timber-framed construction until the now infamous 1983 ‘World in Action’ documentary identified vapour barrier and fire resistance defects that caused the near collapse of the timber framed sector in England and Wales. Since those times, new types of building systems and technologies have been introduced and this article will review the latest modern method of construction – the structurally insulated panel – and consider how residential practitioners can adopt a balanced approach to assessing this relatively new type of construction.

The problems posed by modern methods of construction (MMCs)

Towards the end of the last century, a number of government initiatives attempted to modernise the construction industry, resulting in many agencies embracing new materials and techniques (especially in the social housing sector). Collectively called ‘modern methods of construction’ or ‘MMCs’, these never broke through to the mass private housing market despite their starring roles on TV programs like ‘Grand Designs’.

The ‘noughties’ slipped by and although the house building industry had successfully incorporated new ‘sub-assemblies’ into conventional building methods (for example, plastic plumbing, prefabricated chimneys and timber ‘I’ beam floor joists to name but a few), major builders did not adopt MMC.

Research carried out by the NHBC Foundation (https://www.nhbcfoundation.org/publications/), investigated the potential barriers to these new building methods. In their 2013 publication ‘Building sustainable homes at speed – risks and rewards’, stake holders identified the most significant risks of using fast building methods. The following three concerns were all in the top five:

- The changeable requirements of the mortgage and insurance industries. Many lenders currently lend on MMC dwellings as long as they are covered by a NHBC warranty or its ‘equivalent’. Others do not rule out lending on MMCs and use phrases like ‘considered on a case by case basis’ or they are ‘confirmed as mortgageable by the surveyor’. In other words, the practitioner is left to decide;

- Concerns about the high cost of maintenance. Many MMC systems are relatively short-lived making the sourcing of replacement products difficult if problems occur in the future. Insurance companies also want to know the nature of a building’s construction as several charge a premium for modern timber framed properties. Insurance companies specifically warn applicants that inaccurate disclosure of the true nature of the dwelling could invalidate insurance cover if a claim is made.

- Worries about the health implications of low air impermeable structures. Academic research into the quality of air in tightly sealed dwellings is regularly featured by main stream media.BBC News, the Guardian and the Telegraph are amongst those who have covered the topic over the last twelve months.

A new assurance scheme

In an effort to provide reassurance to the lending community that modern building techniques can provide a minimum life of 60 years, RICS, Lloyd’s Register and Building LifePlans Ltd (BLP), in consultation with the Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML) and the Building Societies Association (BSA) formed the Buildoffsite Property Assurance Scheme or BOPAS for short (http://www.bopas.org/). This Assurance Scheme comprises:

- A durability and maintenance assessment.

- A process accreditation.

- A web enabled database comprising details of assessed building methodologies, registered sites and registered/warranted properties

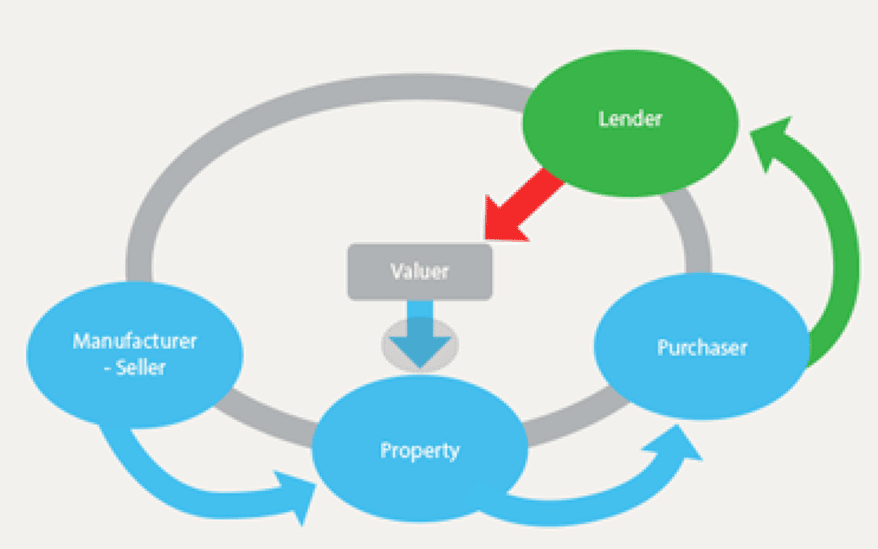

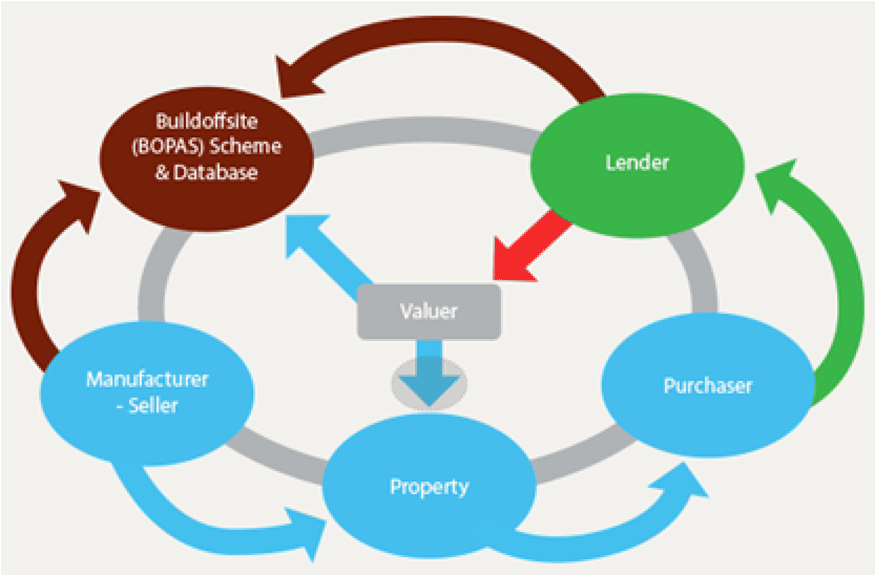

The concept is illustrated in figure one and two. In figure one, the valuer is left to make the lending decision. In figure two, the BOPAS database would provide the necessary assurance of a 60 year life.

Figure One: The current where the lending decision is largely left to the valuer.

Figure Two: The future according to BOPAS. Their database supports the lending decision and provides reassurance to the market.

However, BOPAS promises much but delivers little of practical benefit. A quick review of their website reveals few the inclusion of few contractors/developers (less than 30) covering a relative small number of housing developments (less than 60 sites across England and Wales). Some of the sites are small and much of the data incomplete. Although it may be early days, the BOPAS initiative falls short of giving valuers universal reassurance.

If it’s broke, fix it

Just when the MMC initiative was in danger of becoming a damp squib, two developments have lit the fire under the prefabrication pot.

The first, published in October 2016 was the report commissioned by the Construction Leadership Council, at the request of government by quantity surveyor Mark Farmer. Sub titled ‘Modernise or die’, this review of the house construction sector made a number of recommendations including one that calls on the government to promote the use of ‘pre-manufactured solutions’ to house construction through policy measures.

The second was the government’s own white paper published in support of the proposed Housing Bill that promised to fix ‘our broken housing market’. Amongst its proposals is the aim to support and increase the use of ‘modern methods of construction’ as a way of increasing the supply of new housing.

Prefabrication is dead, long live prefabrication!

To some extent, the sector had already picked up the baton. For example, Legal and General have set up L&G Homes that aims to do for housing ‘…what Henry Ford did for the modern automotive industry’ by ‘providing precision engineered factory manufactured houses’. They have set up one of the largest modular housing factories in Europe and are currently building support for their ambitious plans within the lending community https://www.legalandgeneral. com/modular/). They are not on their own. Housing associations are linking with Chinese multinationals and small and medium sized manufacturers are pitching in the self-build markets. These latest developments all have a common thread: the systems are based on modular pods built and finished in the factory and fixed together on site.

Implications for residential practitioners

Whatever our opinion of MMCs, residential practitioners are having to value and assess these newer forms of construction now. Faced with lukewarm attitudes from both lenders and insurers, how can practitioners strike the balance between properly advising clients, protecting our own liability while not standing in the way of innovation and change?

Structurally Insulated Panels – the new kid on the block

Rather than running through all the different types of ‘modern methods’, I will ‘cut to the car chase’ and focus on identifying and assessing structurally insulated panels (or ‘SIPs’ for short) because:

- They are at the heart of many of the new modular and prefabricated systems currently being launched in the market place, and

- They are different to most other types of prefabricated timber frame panels

Why are SIPs different?

To answer this question, it is important to understand the nature of a SIP and how they differ from the ‘traditional’ timber framed systems.

Timber-framed wall panels usually comprise of vertical timber studs, soleplates, headplates and noggins all sandwiched between varieties of boards. The resulting voids are usually thermally insulated in the factory by injecting or placing thermal insulation within the timber framework.

SIPs on the other hand, consist of two high density facings (typically orientated strand board or OSB) bonded to both sides of a low density, cellular foam core. Often called ‘stressed skins’, these boards enable the relatively lightweight SIP to support high loads and remove the need for internal timber studding as the boards themselves transfer the weight of the building to the foundations. Although the majority of SIP systems use OSB skins, a small number have started using fibre reinforced, cement-based composites.

In the UK, SIPs are available with a number of different insulation cores; expanded polystyrene (EPS), extruded polystyrene (XPS), polyisocyanurate (PIR) and polyurethane (PUR). Thermal performance is further improved because there is little or no internal studding to create cold bridges that characterise conventional timber frame panels.

However, the strong structural bond between the OSB boards and the insulation is central to the SIP’s load bearing ability. If this was to breakdown, the panels could become unstable. It is this feature that gives rise to concerns over SIP’s durability and many of the regulatory and installation requirements are focused on keeping the OSB boards damp free.

SIPs and dampness

Apart from the various standards and codes of practice that govern the design and installation of SIP systems, there is little information in this country about the durability and performance in use but there is more information in the USA where SIPs have been used since the 1950s. An internet search revealed sources that ranged from a federal investigation into failed SIP panels to public housing in Alaska through to numerous articles by builders and inspectors discussing failed OSB ‘skins’. Dampness seems to be the major factor in the reported problems.

The biggest challenge is the repair of the SIP once the skin has failed. Where the breakdown of the OSB board is localised and limited, the panel can easily redistribute the loads around the problem. But where the failure affects the bond between the OSB and the foam core, the strength and stiffness of the whole panel can be affected. In the worst cases, temporary shoring may be required.

Once this happens, the repair is complex. Because the OSB skins transfer load to the foundations, simply cutting out the affected board and gluing in another piece is not an option. The matter would have to be reviewed by a structural engineer and the repair could involve disruptive panel removal and replacement or alternatively a repair using conventional load bearing studwork. It is interesting to note that many of the reported failed panels in the USA had the cladding fixed directly to the surface of the SIP itself.

SIPs and ventilated and drained cavities

Due to problems of this type, most SIP manufacturers, trade associations and warranty schemes in the UK require drained and ventilated cavity between the SIP panel and the cladding. This can range from 20mm cavity for timber cladding, brick slips and thin renders to 50mm for conventional masonry skins. Whatever the type, the cavities should be drained and ventilated by weep holes above all cavity barriers and along the base of the walls. The final barrier against dampness is usually the breather membrane fixed to the surface of the panel.

Although the requirement for a drained and ventilated cavity is plainly stated, Code of Practice published by the UK SIP Association (December 2013) state that in the majority of cases, the cladding systems are installed by someone other than the SIP manufacturer and erector. It is therefore important that the cladding installers follow the SIP manufacturer’s guidance and, where applicable, their standard details.

SIPs and flooding

This vulnerability to dampness can affect the SIP panel when subject to flooding. In their Engineering bulletin 10 (Structural insulated panels construction – November 2015), the Structural Timber Association point out that water can ‘…wick up through the end grain of the board’ and if the panel gets wet, the board will usually dry out after the building is heated. However, the bulletin goes on to say that if the panel becomes saturated ‘then replacement or remedial work may be necessary and specialist advice should be sought’. This makes it clear that SIP buildings will be particularly vulnerable in areas prone to flooding. Although Kingspan (a major manufacturer of SIPs in this country) have published a technical bulletin about flooding and insulation (July 2016), the publication concentrates on the effects of water on the insulation in conventional cavity walls. It mentions nothing about the effect of flood water on the bond between the OSB skin and the insulation in a SIP structure.

The UK SIP Association also highlight the vulnerability of timber based products to dampness and highlight the need to keep the base of the building above external ground level by at least 150mm. However, they point out this can be difficult around entrances where level access is required and in this case, masonry upstands may be needed.

Assessing a SIP property

So what does this all mean to those professionals who are left with the problem of valuing and assessing the condition SIP buildings? In an effort to provide broad guidance for residential practitioners, I have identified a three-stage protocol.

- Identify whether the property is built using a modern method of construction.

- Identify whether the modern method incorporates any SIPs.

- If it is a SIP system:

- Does the property have the benefit of an appropriate 10 year warranty and building regulations approval?

- Does it have a drained and ventilated cavity?

- Is it in an area that is likely to be affected by flooding?

These will be explained in more detail below.

Identifying the property is built using modern methods of construction

Practitioners have been distinguishing between traditional masonry buildings and those built using timber frames for many years (for energy performance certificates if nothing else). Although many MMC types are different to timber frames, some of the features are similar. Here are a few helpful hints:

Desktop study and local knowledge – many practitioners keep a ‘watching brief’ on all new developments in their area and this can help identify those properties built using MMCs. Other useful information includes:

- The likelihood of MMC being used increases after 2000.

- Smaller, one-off developments will often incorporate modern methods as self-builders prefer the ‘packaged’ approach. Beware! One-off, self-build developments may not have the warranties required by mainstream lenders.

- Make good use of ‘seller’s’ questionnaires and ask the vendor specifically if the property was built using modern methods of construction and/or prefabricated building systems. The answers can be revealing.

Inspection of the property

This section assumes you are carrying out a standard inspection for a level two inspection without any ‘opening up’ (for example, a HomeBuyer Report or a Home Condition Survey).

Externally

- Window position – many MMC/timber-framed structures will have windows fixed to the frame and not to the outer leaf. This may result in deeper external reveals when compared to brick/ blockwork construction (see figure 3).

- Expansion joints – MMC/timber framed structures often have mastic filled movement joints under the windows where clad with masonry.

- Cavity weep holes – all types of cavity construction will have open perpends/weep holes to allow cavity drainage and ventilation. These should be visible at the base of the external wall at approximately 1500mm centres and over openings and at other locations (for example, above cavity fire barriers at each storey height). SIPs with a cavity are not different.

- Wall thickness – this is no longer a clear indicator. For example, masonry cavity walls can have very thick internal concrete skins while SIP panels can have slim claddings and no cavity resulting in a thinner overall wall construction – so keep an open mind!

Figure three: This timber framed property has a deeper reveal to all openings

Internally

- The gable wall and party walls in the roof space – a timber frame building is likely to have a timber spandrel panel forming the inside of the gable wall at roof level – see figure 4). On the party wall, it may e clad with plasterboard. For SIP building or other similar MMC, you are likely to see a plain OSB face to both the gable and party wall panels.

- Solid lintels above openings – Traditionally, tapping on the wall above a window opening can help distinguish between dry-lined conventional masonry walls and a timber frame structure. This is because masonry walls with batten-mounted dry lining will sound hollow but timber framed inner leaf will usually have a timber lintel immediately above the opening and so will sound solid. However, many masonry, timber framed and other panel structures are dry lined to provide a ‘service’ zone so don’t jump to early judgements.

Figure four: Timber spandrel panel to the gable wall of a timber framed property.

Does the modern method of construction incorporate any SIPs?

This is more difficult because if SIPs have been used to form the roof structure (which is likely), then the resulting ‘room in the roof’ will prevent that easy insight into the nature of the construction a conventional roof space usually provides. Despite this, there are some indicators that can help.

SIP roof sections are usually supported on substantial purlins and ridge beams (see figure 5). Because the SIPs are usually factory finished with a suitable sheet material, this sheet will pass behind the purlin. If the roof was constructed on site, the ceiling finish would usually butt up to the purlin – a subtle but important difference.

As mentioned above, if there is a roof space SIP panels will show OSB panels rather than plasterboard. building control approval should include a final completion certificate.

Does it have a drained and ventilated cavity? Assuming you have identified the property to be based on a SIP system, the next question is whether it has a drained and ventilated cavity between the cladding and the panel itself. If it hasn’t, then it will be vulnerable to dampness problems and is unlikely to have an appropriate warranty as all of those described above require a drained and vented cavity.

A drained and ventilated cavity will have the following characteristics:

- Brick slips, thin render systems and other cladding types that have a ventilated and drained cavities will have the following characteristics:

- Weep holes in the usual places including over openings and above any cavity fire barriers at storey heights

- A ventilated gap along the bottom edge of the cladding covered with insect mesh at or around DPC level. At this point, there is likely to be a difference of at least 40mm between the face of the wall below and above the edge of the cladding.

- Masonry outer skins (brick, stone and rendered blockwork) will have weep holes in the usual places and as described above and figure 6.

- Claddings that have a drained and ventilated cavity will usually incorporate a DPC approximately 150mm above ground level.

Cladding fixed directly to the SIP panel without a drained and ventilated cavity will not have any of these features.

Figure five: This SIP roof is supported by very large purlins

Figure six: Drained and ventilator cavities will show weep holes and DPCs at low levels.

If it is a SIP system

If you decide the structure of the property includes SIPs, ask the following questions:

Does the property have the benefit of an appropriate 10 year warranty and building regulations approval? The NHBC, Premier, Zurich and BOPAS warranty and insurance schemes are the most common types in the market place. Most commentators agree that these would provide reassurance to valuers and lenders in the future especially if backed up with building control approval. The building control approval should include a final completion certificate.

Is it in an area that is likely to be affected by flooding?

Although residential practitioners do not carry out a flood risk assessment as part of the normal level of service, local knowledge should reveal whether the site is in an area vulnerable to flooding (both river based and surface water). This information will usually be obtained from the Environment Agency website and based on the normal postal code search.

If the property is in an area identified as being subject to river or surface water flooding, the suitability of such a building system must be questioned.

Reporting to the client

Making a decision

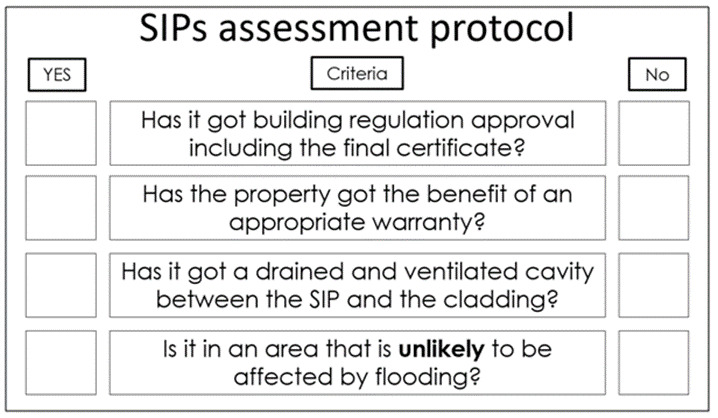

Once this information has been collected, the following series of questions may be of use. It adopts a very simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response to four questions and may help practitioners take a view. There is no numerical route to the ‘right’ decision although a full set of ‘no’ responses may suggest a conclusion!

Although a professional judgement will still have to be taken, it should give you a logical and factual trail to show clients and lenders that an objective approach has been

followed.

Figure seven: the BlueBox partner’s SIP assessment protocol

Reporting to the client

Like all assessments, practitioners should aim for a balanced decision. It is important to raise legitimate concerns about these new and emerging technologies without resorting to a biased and ‘luddite’ inspired decisions just because something is new and unfamiliar. The following phrases may be helpful.

Generic MMC phrase – satisfactory

The following phrase is may be suitable for those MMC based properties that appear satisfactory (usually under E4 in the HBR):

The property is built using modern materials and techniques with some parts pre-fabricated in a factory and transported to the site. This particular method is known as (insert name or generic type). The main walls are formed with (describe the details).

Condition rating 1. No repair is currently needed. The property must be maintained in the normal way.

Some properties built with modern materials and techniques have encountered difficulties when offered as security for normal mortgage lending and this might affect saleability in the absence of appropriate assurances and warranties.

You should ask your legal adviser to check whether this construction method is included in a certified scheme and that an appropriate structural warranty is available (see Section I2).

Generic MMC phrase – not satisfactory

The following set of phrases may help formulate appropriate response where the property does not ‘pass’ the proposed assessment protocol (usually under E4 in the HBR):

The property is built using modern materials and techniques with some parts pre-fabricated in a factory and transported to the site. This particular method is known as (insert name or generic type). The main walls are formed with (describe the details). There are

a number of concerns:

- It is unlikely the property has appropriate assurances and warranty cover and/or building regulation approval;

- The structure of the property is not properly protected from dampness by the external cladding/walling;

- The property is in an area vulnerable to flooding that may affect the structure of the property.

- These are potentially serious problems (see J1 Risks to property).

Condition rating 3 (further investigation).

(Adjust the following phrases to suit)

Some properties built with modern materials and techniques have encountered difficulties when offered as security for normal mortgage lending and this might affect saleability in the absence of appropriate assurances and warranties.

I noted a number of features that indicate the property may not meet the expected standards (briefly describe these).

You should ask an appropriately qualified person to investigate these matters and provide you with a report on the suitability of this form of construction before you commit to purchase.

You should ask your insurance company if this problem would affect your ability to get insurance cover for this type of property in this location (see section I2).

You should ask your legal adviser to check whether this construction method is included in a certified scheme and that an appropriate structural warranty is available (see Section I2).

References

The following references may be useful:

A variety of technical papers are available for download from a company called SIP Building Systems at:

http://www.sipbuildingsystems.co.uk/technical-papers.php

The Building Research Establishment (BRE) have published the following:

- An introduction to building with Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs). IP 13/04

- Modern methods of house construction – a surveyors guide. Keith Ross. BRE Trust 2005.

Other useful sources of information include:

- Flooding & Insulation: steps to improve the flood resilience of buildings. Technical paper published by Kingspsan. July 2016.

- Structural insulated panel construction. Structural Timber Engineering Bulletin 2015. Structural Timber Association.

- Surveys of Timber framed houses. Wood Information Sheet 10. TRADA technology. 2015